Dick Seaman

Richard John Seaman-Beattie was born in Chichester on the 3rd February 1913. His father William Beattie-Seaman was a wealthy Scotsman who had married Dick’s mother two years before. Lillian Graham Pearce was the product of a late Victorian upbringing of privilege. Doug Nye and Geoffrey Goddard in their book “Dick and George: The Seaman-Monkhouse Letters” (which, if anyone has a spare £200 laying around and fancies getting me a gift, I’d love a copy of) wonderfully describes Lillian as a “ferociously pompous grande dame of absolutely the stiffest corset.” You wonder, with a description like that, how poor old William ever got the corset undone… After losing their house, Kentwall Hall in Suffolk, to a Zeppelin raid in 1915, Lillian moved them to town and Ennismore Gardens, Prince’s Gate. Sent to school at Broadstair’s and Rugby, he didn’t put much work in until the exams for Oxford came up and, having crammed like the best of them, won a place at Trinity College. Having got into Oxford, he promptly left as soon as possible to race his Riley. At his first event, the Shelsley Walsh Hillclimb he came second to a man in another Riley, Whitney Willard Straight. Straight, then an undergraduate at Cambridge, was an American millionaire and would go on to lead an extraordinary life himself, eventually having a long relationship with Diana Barnato-Walker, the two would have a child together, but never marry. Straight and Dick hit it off immediately and in Straight’s plane (he would later teach Dick to fly) they would travel to events together. Just before his twentieth birthday Dick, in his new Bugatti, lost an argument with a bus at Victoria Station and his parents started to worry even more about their boy. They were delighted when asked what he wanted for his twentieth birthday, Dick had responded he would like a country house. Pleased to be getting their boy out of the city and hopefully on their chosen path to becoming a MP, they purchased Pull Court in Worcestershire for him. Dick was delighted with his present and went straight back to racing. He joined up with Whitney Straight who had just formed his own racing team. Racing a supercharged MG K3 Magnette he won his first race on 26 August 1934, a junior grand prix, the Prix de Berne, in the forests of Bremgaten. Flush with his success, Dick settled down to watch his team mate Hugh Hamilton take part in the full Swiss Grand Prix in a Maserati 8CM. Hamilton would be in a grand fight when he left the circuit, hit a tree and was killed. Hamilton was trying to keep up with the future, Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz teams had arrived and the form book was out the window.

When Hitler came to power, he immediately started to rebuild Germany. The recovery of Germany from the shackles of Versailles and the ashes of the strife that followed the First World War, astonished the world. Germany quickly shrugged off the Great Depression and became an economic power house. It is academic to say, but Hitler’s leadership was viewed around the world with awe. The Royals in England, being of good German stock, were taken in, Edward more than most. In the US, Lindbergh was hailing the transformation of Germany and the rest of Europe tried to follow the lead set in Berlin. The warnings were there, but the world was being blinded by the light. By the time of Dick’s win at Berne in 1934, Hitler had set upon a program of championing German manufacturing and engineering to match his portrayal of the master race. Britain, trying to match this, suffered a distinct lack of funds. The great sporting achievements of the age were privately financed. Reginald Mitchell, Supermarine and the RAF needed the generosity of Lady Houston to pay for the S6B to win the Schneider Trophy outright for the third straight time. Next time you visit the Science Museum and see the Spitfire’s father, remember it was paid for by a rich woman who didn’t like foreigners. Raymond Mays, for British prestige, founded English Racing Automobiles (ERA), to take on the French and Italians on the circuits of the continent. With Bentley no longer flying the flag, ERA, Riley and MG took up the challenge, as far as their budgets would allow. And that was usually in the Voiturette 1500cc class of racing, the GP2 of its day. In 1933 the AIACR, the FIA’s forerunner, announced the rules for next season’s of Grand Prix cars and limited them to 750 kgs. Hitler, never missing a propaganda opportunity, announced the People’s Car and a Grand Prix programme in 1933 and put up 450,000 reichsmarks for Mercedes-Benz to enter their newly developed W25 car. The newly formed Auto Union company (now Audi, but then an amalgamation of the original Audi, DKW, the steam train manufacturer and Horch and Wanderer, two luxury car and engine manufacturers, hence the four interlocked rings on the Audi badge) got Ferdinand Porsche, the People’s Car designer, on board to turn his P-Wagen racing concept into their ca. Auto union then played the politics card by getting driver Hans Stuck, a friend of Hitler and without a seat after getting turned down by Mercedes, to arrange a meeting of Porsche, the Auto Union chairman and Hitler to discuss if it wouldn’t be a better idea, for the greater glory of German of course, to have two Grand Prix teams? Hitler loved the idea, changed the deal with Mercedes and put up a prize of 500,000 reichsmarks for the best team of 1934 and 250,000 reichsmarks each a year to run the programs. This annual fee would grow by ten times by the outbreak of war. Mercedes-Benz were less than pleased by the funding cut but were now doubly determined to win the prize. The W25 was a rather straight forward design for its day, but Porsche’s P-Wagen was revolutionary. Following on from the People’s Car, the car was mid-engined (between the driver and rear axle) for better weight distribution. The V-16 made the lightweight car massively powerful. When the two companies went racing properly, they shocked the racing world. Mercedes-Benz won four races and Auto Union one. The only blot on the copy book was the French Grand Prix where no German car finished and the French dominated. To put this in context, imagine today, two new teams showed up on the grid and where around 5-10 seconds A LAP faster than Red Bull, McLaren and Ferrari, and only got faster each year. Enzo Ferrari, then running the legendary Alfa P3’s in the newly formed factory team of Scuderia Ferrari would watch and learn while his star driver Tazio Nuvolari’s pure skill would allow one or two victories before, in 1938 after getting bored of losing, Nuvolari too joined Auto Union. Even the cars broke from the established order, they no longer wore the racing White all previous German cars raced in, they were left silver (legend has it, both team’s cars were too heavy so they stripped the white paint to get them under the weight limit), The Silver Arrows were born.

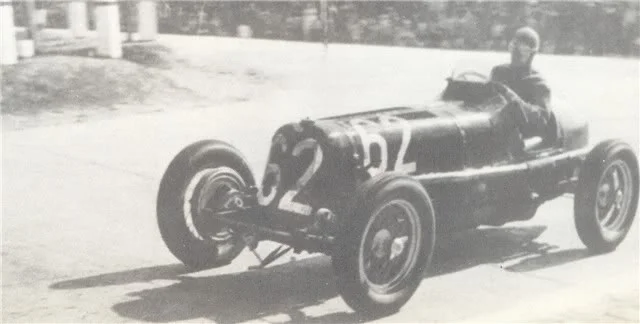

Dick in his ERA

Dick could see which way the wind was blowing. Lillian knew her son and, after hearing of Hamilton’s death, bought him a Gypsy Moth III to try and distract him from racing. Lillian and William were even more happy to hear Whitney Straight was getting married and giving up racing, maybe Dick would follow suit… The stag do for the boys was rather epic and put any notion of Dick giving up racing out of his parents heads. Dick jumped in Straight’s De Havilland Dragon Rapide and together they set off for East London, South Africa, a thirteen day flight both ways, to compete in the South African Grand Prix, which Whitney would win. William was beside himself by worry and telegrammed Dick that he was cutting him off. Before he could return and before his father could act on the threat, William suffered a heart attack and died. Dick, upon his return to his grieving mother, talked her into opening her purse again and to buy his way into the works ERA team, and a 1 1/2 litre car, for £1700. Lillian did as her darling boy asked, and bought him the car. The car was a lemon. It turns out ERA and founder Raymond Mays (who would later form BRM and the car that tried very hard to kill Sterling Moss, the BRM 15, but also later give Graham Hill his first World Championship and Jackie Stewart his first win) sold Dick a poorly rebuilt spare car, Dick couldn’t do anything with it. In a fury, he resigned from ERA, got Lillian to open the cheque book yet again and formed his own team, based out of the garages of his mother’s home in Ennismore Gardens. Dick’s next move was his master-stroke, he hired Whitney Straight’s old mechanic Giulio Ramponi. Ramponi hadn’t just worked for the playboy Straight, he had worked for Enzo Ferrari on his Alfa P3’s. He painted the ERA a very non-British black and later in 1935 returned to Switzerland for the Prix de Berne where he promptly beat Mays and the factory team for the victory at an average speed of 82 mp/h. Dick would win three races in the car before, for 1936, his eyes turned to the Isle of Man and the RAC International Light Car Race.

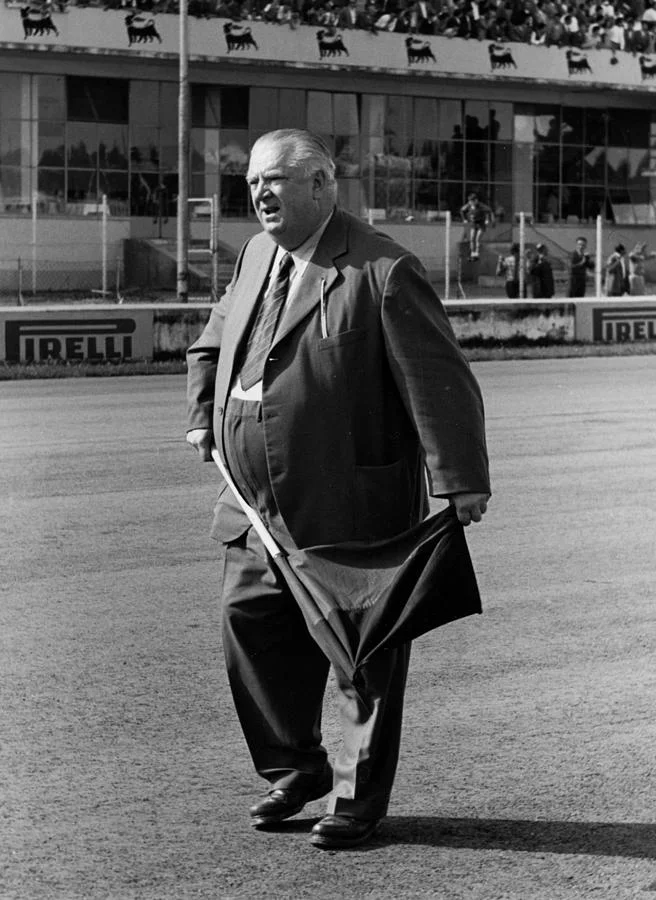

Alfred Neubauer

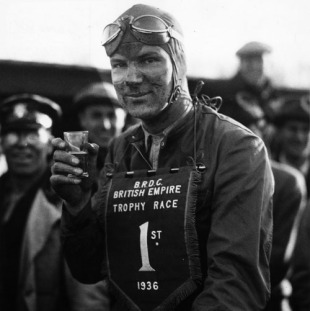

At the prompting of Ramponi, Dick got his hands on a Delage straight 8 car, previously owned by Francis Cuzon, 5th Earl Howe and Tim Birkin’s co-driver for the 1931 Le Mans win for Bentley ( a car which was recently sold by Hall and Hall for a very high, yet undisclosed figure). Romponi rebuilt the car and Dick promptly won the race. The press made the story out to be the boy who showed up in the borrowed car and won out of the blue. The truth is Dick was very good and with Ramponi preparing the car, it was always a winning combination. Dick and Romponi took the Delage to the continent and with all the attention they were generating, Dick caught the eye of someone else, Mercedes-Benz’s team manager Alfred Neubauer. Neubauer had been Ferdinand Porsche’s chief test driver at Austro-Daimler and a not very successful racing driver. Having followed Porsche to Daimler, he created the role of Racing Team Manager for Mercedes-Benz and would stay in the job until 1955. Neubauer was a perfectionist in the grand Teutonic tradition. He drilled the pit crew, drivers, everyone, to perfection He invented the use of pit boards for better communication with his drivers and the result is the role he created is still coveted today. Next time you see Martin Whitmarsh or Christian Horner on the telly, they can thank a fat, failed racing driver for coming up with the idea for their job.

In 1936, Dick was getting great press and winning races at home and all over the continent. In Britain, as road racing was, and still is, illegal, Brooklands was the only place to race. But a man called Fred Craner, President of the Derby and District Motor Club, convinced John Gilles Shields, owner of the Donnington Park estate to allow racing on his land. In 1933 he staged a 300 mile race, which went down well even if only local British racers showed up. In 1936, he did it again, this time the pick up was better, here was a race the Germans hadn’t entered. Dick borrowed a Maserati 8C and with it’s owner Hans Ruesch, they won in style. Neubauer had seen enough and dispatched a telegram, addressed simply “Seaman – Ennismore Gardens”, to London summoning Dick to the Nurburgring for a test in late 1936. The German teams could field one non-German driver each, Auto Union were after Nuvolari, Neubauer wanted Seaman. Lillian hid the telegram. She didn’t want her boy racing and she certainly didn’t want her racing for the people who had turned her country pile into just that in the last war. But, if Dick passed the test and got the drive, Mercedes-Benz would not only pay Dick, but cover the cost of racing. Lillian had spent a staggering £20,000 on Dick’s habit up to that point, or £2m in today’s money. When Dick finally got hold of the telegram, he dashed right to Germany to get his hands on the new W125.

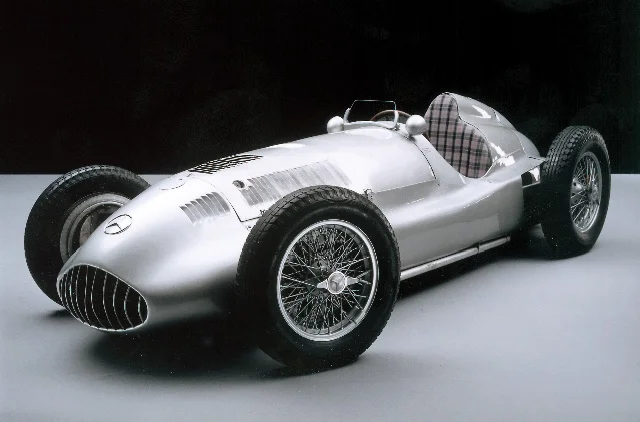

Mercedes-Benz W125

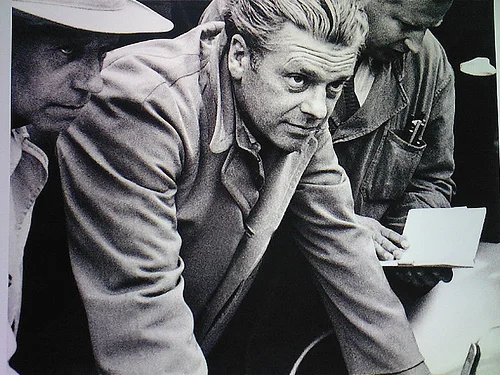

Rudolf Uhlenhaut

The Mercedes-Benz W125 was the first car for the marque designed by Rudolf Uhlenhaut. Uhlenhaut was an Anglo-German engineer and driver and after being put in charge of the racing department in 1936, set off and pulled apart the ageing W25. As a fast driver himself (he would later lap one of his 1955 W196’s faster than Fangio could manage) he knew the inherent problems with the weight and power of the car, which was why Auto Union were winning more often. During the Uhlenhaut’s test of the W25, one of the wheels came off at speed, Rudi drove the car back to the pits as if this was perfectly normal and announced the suspension was so stiff it was bending the chassis under breaking. This, he said, wouldn’t do. His answer was the W125. The car was lighter, had a new suspension system and a brand new in line 8 cylinder engine that produced 595 bhp. When Dick arrived for the test, he was one of 30 drivers competing for a race seat. Dick got one of the race seats with Neubauer’s assessment of the Englishman being “this young man has real talent.” After arriving he telegrammed a friend, George Monkhouse, and told him to join him. Monkhouse (the Monkhouse in the Seaman-Monkhouse letters book you can buy me if you fancy) was a Cambridge graduate and friend of Dick and Whitney, he was also a superb photographer. Dick told George, if he came, he could be a photographer for Mercedes. So George packed his camera in the back of his Bentley 4 1/2 (what else would you have?) and joined his friend at Mercedes. Before George arrived though, Dick had managed to crash his W125 into a tree and cracked his knee cap. He was still getting used to massive increase in speed. Dick’s first race for Mercedes-Benz was the Grand Prix of Tripoli on the 3rd May 1937, where he finished seventh due to engine problems. Before those problems, he’d been in second behind Hermann Lang and ahead of Rudolf Caracciola. Later that May at Berlin, he improved to finish fifth.

Dick had, by now, moved full time to Germany and Dambach on Lake Starnberg. He was also having to fend for himself as Lillian had stopped paying his expenses. His salary and winning where the only thing he had to sustain himself, which was tricky, considering in 1937, German currency wasn’t allowed out of the country. It was on the lake though, that Dick introduced his new German neighbors to a sport they hadn’t seen before, water skiing. The team next boarded the SS Bremen and headed to the States where they competed in and won the Vanderbuilt Cup. Uhlenhaut wasn’t happy with the power coming from his cars superchargers, so he stayed up all night before the race, redesigned and rebuilt the intakes on each car and sent them out to race. Dick astonished everyone by finishing second behind Bernd Rosemeyer’s Auto Union in only his fourth race for the team. When Rosemeyer had pitted, Dick had lead the race. Interestingly, when he had been offered a helmet by the US race organisers, he announced such this were superfluous for a racing driver. The team then packed up to return to Germany, their destination was the Eifel Mountains outside of the little village of Nurburg.

The Nordschleife

The Nurburgring is probably the most famous circuit in the world. Say Nordschleife to any petrol head and you will see them go weak at the knees. Just the thought of the 13 mile, 153 corner circuit is enough to make them drool. This wasn’t the track Dick and new Mercedes-Benz photographer George Monkhouse were heading too. In the 1930’s the Nurburgring was a mile longer, had 7 more corners and no safety protection. The track isn’t called “The Green Hell” for nothing. No other circuit has destroyed more lives than the Nordschleife. In 1937 the entry was massive. Auto Union fielded five C-Type 6.1 litre V16 cars, Mercedes-Benz countered with five 5.7 litre straight-8 W125’s. Ferrari brought two of his Alfa Romeo 12C-36’s and Nuvolari, who had agreed to join Auto Union for 1938. All the cars, factory or Private were either German or Italian, the French, tired of being outclassed, didn’t show up. The race was one only the Nordschleife could give, fast, furious, with crashes and retirements. Dick was one of the retirements. On lap 6 of 22, Dick was in a pack of car dueling with, among others, the Auto Union of Ernst “Titch” von Delius who was 25 and in his third start for Auto Union. As they raced through the forest, they were at around 170 mph, when Titch’s C-Type clipped Dick’s car. They crashed into the forest and Dick was thrown from his Mercedes, the best thing to happen to you in those days. The cars burst into flames. Dick suffered a broken nose, wrist, arm and thumb. Titch would suffer a thrombosis complication from his injuries and die later that day. Rudolf Caracciola, Wolf Barnato’s old foe from Le Mans in 1930, would win the race. Dick would recover enough from his injuries to rejoin the team for the Swiss Grand Prix where he crashed his car during practice. Neubauer tried and failed to convince Dick to tame his all out style, Dick refused. If he wasn’t at ten tenths, what was the point. Not starting the race, he took over Caracciola’s car after it had come in with engine problems. Neubauer’s faith in Dick was rewarded when on Lap 13, the car burst into flames. Dick calmly switched the engine off and waited for the flames to go out. When he came to a downhill section, he bump started the car and continued the race and finished fifth. Dick may have been a hard charger in the car, but he was wholly professional and a cool head in a crisis.

Dick now got the chance to race in the event he wanted to most of all, the 1937 British Grand Prix at Donington Park. This race is one of the markers that made Britain the powerhouse of motorsport it is today, and all because the Silver cars blew the competition away. In Britain in the 30’s, with the road racing ban, no Grand Prix style racing came to these shores. Brooklands, the only purposed built track in the country, hummed to the sound of the rich in Bentleys and ERA’s. When the Grand Prix circus arrived in 1937, they didn’t know what was about to hit them. In Rodney Walkerlay’s book “When the Germans came to Donington” he describes the impact on the snooty ERA bred British hacks:

data-animation-override>

“Away beyond the woods we heard the approaching scream of a well-tuned E.R.A. and down the winding slope towards us came Raymond Mays. He changed down, braked, skirted round the Hairpin and was gone. “There’s the winner,” remarked one of my friends. “Knows this course backwards.” Half a minute later came the deeper note of a 2.9-litre Maserati, and “B. Bira” (Prince Birabongse of Siam, Mays’ nearest rival and a new star in the racing firmament) shot past us, cornering with that precision which marked him as the master he was. “Or him,” said another. We waited again. Then they came. Far away in the distance we heard an angry, deep-throated roaring – as someone once remarked, like hungry lions impatient for the arena. A few moments later, Manfred von Brauchitsch, red helmeted, brought a great, silver projectile snaking down the hill, and close behind, his teammate Rudolf Caracciola, then at the height of his great career. The two cars took the hairpin, von Brauchitsch almost sideways, and rocketed away out of sight with long plumes of rubber smoke trailing from their huge rear tyres, in a deafening crash of sound. The startled Pressmen gazed at each other, awe-struck. “Strewth,” gasped one of them, “so that’s what they’re like!”

Dick would manage 29 laps before a suspension problem would force him out. But as the above quote shows, they were in a class of their own. The British public and press had never seen the like. The sight of the Silver Arrows literally leaping off the brows of hills on the circuit showed where the bar was and just how far the bar had been raised. Back in Germany, Dick was called in for what would for modern drivers be termed a PR day, he was to show the Duke and Duchess of Windsor around the Mercedes-Benz factory in Stuttgart.

Mercedes-Benz W154

The rules were changed for 1938, so Rudi Uhlenhaut went back to the drawing board and came up with another world class design, the W154. The new rules stated that supercharged cars could only have a maximum capacity of 3000cc, so they built a new V12 engine that produced 470 bhp coupled to a new five speed gear box. The car was unveiled by Hitler at the 1938 Berlin Motor Show. It’s also now that Dick Seaman’s story starts to split, depending on which biographer you read. Dick had written his mother after his arrival in Germany bemoaning the state of Britain in the international eye and he praised Hitler, “Hitler stands no nonsense. He won’t have any slackers about. Everybody has got to work. Consequently he has remade and reorganised the country, and that is why they believe in him and rally round him. It’s about time Hitler took over Austria too, and made them sit up and pull themselves together. The dirt and squalor and laziness in the country are beyond words. Why, there are men there who ask nothing better of life than to sit about all day over one cup of coffee in a cafe!” Lillian replied, as would most in Britain in 1937, “How impressive it is to see the way in which Herr Hitler stands no nonsense from shirkers, wastrels and communists.” Depending on your viewpoint, whether or not Dick had fallen under the spell of the shiny bubble that Nazi Germany was showing to him and the world, is difficult to state which side of the fence Dick was on and his biographers have a tricky time nailing it down. Lets face it, up until this point in time, as we stated earlier, the world was holding Germany up as an example to follow. Dick’s bubble was bursting though. He’d made a sarcastic comment about the pomp with which the car was unveiled to friends and he would go further the following year when Hitler would unveil the 1939 car and Dick would comment to Monkhouse, “At the end of a 17 minute speech, plush curtains at his back were swept aside, disclosing to a fanfare of brass instruments, the main exhibition hall behind. In fact, I doubt Cecil B de Mille could have done it much better himself!” Despite the fanfare, Dick’s car wasn’t ready for the first race at Pau, where the race was won by Rene Dreyfus in a Delahaye. The Frenchman would dine out on that win for the rest of his life. The fact the race was non-championship and the Silver Arrows used it as a test, seems to have been lost on him. Nuvolari would win championship races for Alfa against the full blooded Silver Arrows, before he too joined them. By June of 1938, Dick hadn’t had a race start as Mercedes were struggling to iron out the teething issues with the W154.

Erica Popp

So he did the party circuit and championed his employers wherever he was sent, just as drivers have done ever since. At an event thrown for British companies by BMW at the Preysing Palace in Munich, ironically next door to the beer hall where Hitler had failed in his 1923 putsch, BMW chairman Franz-Josef Popp introduced Dick to his 18 year old daughter Erica. Erica fell in love with the dashing English driver. What probably helped was that nine days later, Dick would be a German National hero.

The Team. Left to right: von Brauchitch, Neubauer, Dick, Lang and Caracciola

The 1938 German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring was being carefully staged. A few weeks before at the French Grand Prix, Mercedes entered four cars in what would have been Dick’s first start of the year. The French limited the German teams to three cars each. Mercedes responded by filling the top three places, Manfred von Brauchitsch taking the win and the third placed W154 of Hermann Lang finished 9 laps ahead of the French Talbot of Rene Carriere. As the Silver Arrows arrived for their home Grand Prix, Mercedes and Auto Union were fielding their best, four cars each. Germany had to win this race and the order from the party was that it had to be a German driver. For Nuvolari and Dick, the two foreign drivers, this must have been a pain. Sports events in Germany in the late Thirties were meticulously stage managed. After Jesse Owens performance at the 1936 Olympics, Germany responded by making sure Germans had the best of everything to prove the mastery of the Master Race. Only one non-German had won the German Grand Prix since 1931 and that was Tazio Nuvolari in 1935, but now he was in a German car. As the Nazi Party dressed the length of the 14 mile Nordschleife in the swastika, Uhlenhaut and Neubauer prepared the team. In qualifying, the W154’s claimed the first four spots on the grid, Dick was on the front row in third. Auto Union claimed the next four. On race day, 300.000 people crowded around the circuit and Neubauer issued team orders that the Mercedes cars would hold position from the start, Dick was told under no circumstances was he to pass von Brauchitsch or Lang ahead of him. The race started according to plan, Dick, in the number 16 car, set the fastest lap of the race, with a time of 10 minutes 9.1 seconds on lap 6 then, ten laps later after Lang’s car had dropped out with an engine problem, holding station behind von Brauchitsch and in second place, he followed the German into the pits for tyres and fuel. As Dick sat in his car and watched the action around him, the fueller on von Brauchitsch’s car spilled the high octane methyl alcohol/benzene mix fuel over the exhaust of the car and it promptly burst into flames. As the team pulled von Brauchitsch from the car and put the flames out, Dick sat in number 16, arms crossed, while is car was pushed out of the way of the flames.

Dick leading the 1938 German Grand Prix

If you watch the Pathe footage HERE, he goes nowhere until Neubauer is seen running towards waving his scarf at Dick to go, just as Caracciola is seen pulling in behind Dick. Dick didn’t need telling twice and disappeared into the distance. A crispy von Brauchitsch would jump in his foam cover car and give chase, but would retire on the next lap. Caracciola and Lang would share the other remaining Mercedes and try and catch Dick but they couldn’t and Dick would win by four minutes. As Dick returned to the pits, he was mobbed. Neubauer and Uhlenhaut slapped him on the back and pumped his hand, his team-mates did likewise, they were all delighted for Dick.

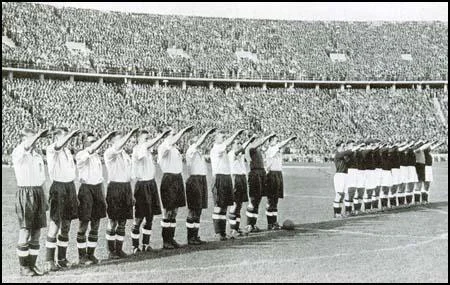

Seaman and The Salute

Next he was taken to the podium on the pits complex and a massive winner’s wreath covered in swastikas draped over his neck by Major Adolf Huhnlein,who announced him to the crowd while the German anthem was played followed by “God Save the King”, during the former, Dick raised his right arm in a half hearted Nazi salute. Cue lasting controversy. Was this Englishman a closet Nazi? He raced for a Hitler backed team after all. Lets look again at the context. He was a determined sportsman in an age where the best teams in the world were German, to win a Grand Prix and have a chance at the European title (the World Championship of the day) he needed a Silver Arrow. All of the world was looking at Germany as the model for recovery, only a few were trying to make public the atrocities that were only just starting. Being seen to play with a straight bat was the order of the day and Dick wasn’t alone in this.

The England Football Team’s Darkest Moment

Only the month before Dick’s win, the England Football team gave the same salute before Hitler at a match in Berlin’s Olympic stadium. For me, the telling point is this. George Monkhouse was taking a photo of Dick on the podium, heard Dick turn to his friend John Dugdale of The Autocar and, as the anthems blared out, whispered “I wish it had been a British car.” Dick was 25 years old, at the height of his career and his fame was rocketing. German newsreels heralded his triumph and showed images of him giving the salute and ended with a portrait of him flanked by ones of Hitler and George VI. In Britain Pathe did the same using the immortal phrase “It was a German team and a German car but who cares! The driver was British.” The hype was well founded, no British driver had won a Grand Prix since Henry Seagrave won in a Sunbeam at Tours in 1923. Dick’s fame at home and abroad was in no doubt, and it always helps to have a beautiful woman on your arm.

Lillian heard the news in Britain and Dick invited her to Germany after the race to meet Erica. Lillian, the incredible snob that she was, proclaimed Erica a “goddess” and was thrilled at the society she kept and the family she was from, the Popps were aristocrats. Erica’s father was friends with the highest members of the Nazi party, Erica was essentially a princess. Seeing the German newsreels championing her son “Der Englander”, she was overwhelmed, she would later write, “I thought, there can be no war. The German people are a friendly nation. They do not want war…” Lillian went home and Dick and Erica went to Switzerland for the Swiss Grand Prix on the Bremgaten track Dick had won on in the lower formulae. Dick put his Silver Arrow on pole and led until it started to rain. Then the old Regenmeister Caracciola caught and past him. Dick would finish the race in second, the only other car on the lead lap. September 1938 would be a momentous month. Dick’s soon to be father in law asked Dick to race one of the BMW 328’s being prepared for RAC Tourist Trophy at Donington Park. Dick agreed and took his number 16 W154 to Monza where limped out of the race with engine problems. As he flew back to Britain for the TT, Neville Chamberlain arrived at Heston with his piece of paper and declared “peace in our times.” Lillian started having reservations about her son and Erica. If there was war, how could she cope with half German grandchildren? Dick’s adventure in Erica’s daddy’s 328’s didn’t go well. All the factory cars had engine issues and Dick finished in 21st place. The next month saw him bring his real car to Donnington. The 1938 British Grand Prix had been delayed fortnight night due to the Czech crisis, but the race on the 22nd October 1938 was a classic. Tazio Nuvolari, fresh from his win at his home race at Monza was in excellent form. Dick was determined grab his second win of the year. Things didn’t start well for Nuvolari, he had hit a stag that had wandered onto the circuit during practice and broke a rib. Strapped up under his lucky yellow jersey, he lead the way in the race, Dick giving chase, but it was not to be.

Dick passes Billy Cotton’s ERA – Donington GP 1938

With the Auto Unions literally flying off the hills around Donington, they were untouchable. Dick’s W154 got caught up in an oil spill on what is now the Craner Curves, spin off and stalled. Nuvolari would take the win. Dick would end the season in fourth place behind his Mercedes-Benz team mates. But he had laid down his marker, to the point where his team mates were having words with Neubauer about not keeping Dick on for 1939. Neubauer ignored the and signed Dick to another years contract. Dick went into the off season with just one thing on his mind, Erica. Despite his mother’s misgivings, they married at Caxton Hall in Westminster on 7th December 1938. Lillian wasn’t happy and the press were already turning against Germany, so it was a quick and quiet affair. The happy couple then headed to the Alps for a winter’s skiing. They were the social couple of the season. They loved going to the cinema together and dancing. They were the darlings of German society and they loved it. 1939 proved a crisis for Dick. His old friend Francis Curzon, the fifth Earl Howe, had told Dick, for sporting reasons, to stay with Mercedes-Benz, other friends, pointing out the worsening political situation, begged him to come home. Dick responded that he had no political feelings so wouldn’t base his choices on them. He would race on for the three pointed star.

At Pau, only listed by Mercedes-Benz as a reserve driver, he would set the pole time in practice, but not race. At Tripolli, Mercedes-Benz would unleash the awesome W165 for the only time. The 1 1/2 litre Voiturette variant of the W154, with a supercharged V8, would take pole, fastest lap and victory in the hands of Caracciola. Dick would not get to race the car. Heading back to Germany he would get his hands on this epic car for a documentary about the Silver Arrows. The director would lavish time on “Der Englander” but Dick was in a foul mood. The week before at the Eifel Grand Prix, he over eagerly dropped the clutch at the start and would be forced to retire a lap later when it broke for good. Much like Senna needed to beat Prost in the 80’s, to set a marker, in the 30’s Caracciola was that marker. The Regenmeister was the team leader and the man to beat. When the circus arrived at Spa for the Belgian Grand Prix in late June, Dick knew he had a chance to prove his skill to his team leader, it was raining.

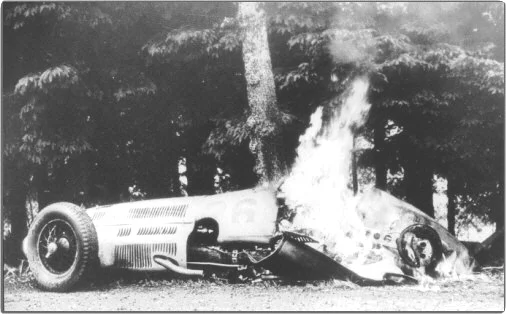

Spa-Francorchamps in the 30’s was a monster. An 8 mile loop that was brutally fast. The modern circuit keeps the famous corners like Eau Rouge and Blanchimont, but much like the Nurburgring, one mistake usually cost you your life. Dick brought Erica with him to the race. Dick, his W154 emblazoned with the diamond encrusted badge Mercedes-Benz awarded their winning drivers with, was determined to show his win the year before wasn’t a one off. Before the race, Erica and Dick had made plans to go to the movies together later that evening, and on the circuit, the rain poured down. After the start and the blast through the La Source hairpin, down the hill and up through Eau Rouge, Dick found himself down in sixth place. He put the hammer down and started to catch Caracciola in the lead. On lap eight he was up to fourth behind his team-mate Lang and the Auto Union of Hermann Muller. Lang waved Dick through and when Muller pitted, Dick set about chasing down Caracciola. Then something unthinkable happened.

Dick Seaman in the wet at Spa, before the crash.

Under pressure from Der Englander, Caracciola made a mistake and slid off the track and into a ditch. Dick was alone in the lead, but true to his nature, he pushed harder. Four laps later he had a 31 second lead over Lang. Thinking of the races he’d been forced to miss at the beginning of the year, Dick wanted to dominate the race. In true Spa fashion, part of the track was starting to dry, while the other half was still soaked. Coming up to La Source, Dick aquaplaned off the circuit and hit a tree. He was travelling at around 200 kph when he hit the brakes. The car hit a tree and Dick was trapped in the cockpit. His fuel tank had ruptured and before the two Belgian police officers that were running to the scene could reach him, it burst into flames. The locals pulled Dick from the car, but due to the nature of the track, the Mercedes team doctor and ambulance took an age to get to the scene. Meanwhile, the race continued. Alfred Neubauer would later write of the crash, “Ninety-nine times a driver takes a bend at precisely the same angle and precisely the same speed. Then the hundredth time he wants to go one better, to cut a second off his time and he puts a shade more pressure on the accelerator. That shade is fatal.”

“That shade is fatal.”

Eventually he made it to hospital, but he was terribly burnt. The designer of his car Rudi Uhlenhaut, Neubauer and Erica were waiting. In great pain, he again, as he had done after his Monza and Nurburgring crashes blamed himself and not his machine. To Uhlenhaut he said “I was going too fast for the conditions, it was entirely my fault, I’m sorry.” Rudi left the room in tears. When Erica came to see him, he smiled at his nineteen year old wife and said “I’m afraid but you will have to go to the cinema alone tonight darling.”Before his father had died he had set-up two trust funds for Dick which totalled in today’s money £11m. He was not allowed to access these funds before his 27th birthday. Dick would die later that night. He was 26 years and 5 months old. On the 30th June 1939, the great and good of the racing world, including the team members from Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, gathered at Putney Vale cemetery to lay Dick to rest. The papers mourned his passing, the Motoring Transport Press ended their obituary “Now he, too, has met the destiny of racing drivers.” Hitler sent a huge wreath to the funeral. Mercedes sent a missive out to all their dealerships around the world, they were all to display a picture of Dick in the windows of their showrooms. Mercedes-Benz continue to pay for the grave and it’s upkeep today. His widow would survive the war and move to America, marrying a succession of millionaires. Erica would pass away in Florida in 1990.

The effect of “Der Englander” on Mercedes-Benz was profound. In 1950, when they were allowed to develop a racing program following the Second World War, Alfred Neubauer and Rudi Uhlenhaut were given their old jobs back. Uhlenhaut designed the W196 for the 1954 World Championship and Neubauer rebuilt the team. They hired Juan-Manuel Fangio, teamed him with, among others, Dick’s old team-mate Hermann Lang and the impact of the car in 1954 was the same as twenty years before. The car was light years ahead of the Maserati 250F’s, Vanwall’s and Ferrari 625’s of the day and dominated the season. But, just like the last time Rudi and Alfred went racing, a young Englishman caught their eye. His name was Sterling Moss.

Like Dick, when he was approached to join Fangio for 1955, Moss didn’t think twice. He would famously win the British Grand Prix at Aintree with Fangio on his rear axle. Moss would finish second in the championship and win the Mille Miglia in Uhlenhaut’s epic 300SLR at an average speed of over 97 mph. Mercedes-Benz would withdraw from racing at the end of 1955, after Pierre Levegh’s 300SLR was launched into the crowd at Le Mans killing him and 82 spectators. It remains motorsport’s worst disaster. The three pointed star wouldn’t return to racing for another thirty years.

“Der Englander” cast a long shadow though. When Jackie Stewart crashed his BRM at Spa in 1965, as he was trapped in his car with fuel soaking through his overalls and as he waited while Graham Hill fought to get him out of his car, his thought’s went to Dick who had met his end in the same way at the same track nearly thirty years before. He was determined not to suffer the same fate. He would race the rest of his career with a spanner taped to his steering wheel so he could escape his car and would campaign, even today, for greater safety in all Formulae of racing.

During his lifetime Richard Seaman was a Nazi propaganda hero and British sporting icon. In his death he was probably saved the most impossible choice anyone could ever face, to pick a side in a World War that his heart sat on both sides of. His great friend Whitney Straight would join the RAF and fight through Norway and the Battle of Britain. Shot down, he would escape his POW camp and make a home run. Later he became an Air Commodore and Chairman of Rolls Royce, where he would try to sue Soviet Russia for copying the Nene jet engine which would power the Mig-15 fighter. While Dick lay in Putney Vale cemetery, London would burn, bombed by aircraft powered by Mercedes-Benz and BMW engines. It would have broken his heart. In Bedazzled Peter Cook’s Spiggot gave Dudley Moore everything he desired, with a twist. When Hitler’s Silver Arrows came knocking they gave Dick a taste of the success he craved, but literally at the cost of his soul and a payment of a fiery end. Wolf and Dick are two quintessentially British sporting heroes. Both are relatively forgotten today, but both did more for creating the British Motorsport industry that dominates Formula One and all other forms of the sport today. Mercedes-Benz even build their Formula One cars in Brackley in Northamptonshire. These two men went to incredible lengths for their dreams, one financially and one morally. Dick may well have meant it when he said he didn’t consider politics when it came to his life, racing drivers are wonderfully self centred. But it would be naive to say he didn’t feel which way the wind was blowing. He’s a hero to me because he chased his dream and damned the cost. That takes a wonderful spirit and determination. But, in life and love, the cost is always there. Dick was handed the apple and he bit large. I think as he laid in his hospital bed in incredible pain and looked into the eyes of his beautiful young wife he saw that the apple was truly full of worms. The choice is presented to us all each day, sometimes that final step may feel worthwhile, but unlike Faust, I believe that what we see now is not the sum of it all and like all bright and shiny things, once you see past it, the disappointment is like a mouthful of worms. Bedazzeled wasn’t named Bedazzeled for nothing.

Leave a Reply