Brigadier-General Sir Harry Flashman VC KCB KCIE was Victorian Britain’s greatest Hero. Despite being expelled from Rugby School for drunkenness, an event that Thomas Hughes recounted in Tom Brown’s Schooldays, Sir Harry turned his life around. Commissioned into the 11th Light Dragoons in 1840, Sir Harry served with distinction from the retreat from Kabul in 1842, charged with both the Light and Heavy Brigades at the Battle of Balaclava, won his VC for his actions in the Indian Mutiny, fought on both sides of the American Civil War and on battlefields from China to South Africa. In his three volume autobiography, of which only two were published (the third of which was pulped by Disraeli over a tax disagreement), he told the tales of his service to Queen, Country and the expansion of empire. His reputation, fortune and memory were sealed. Until, that is, 1965 when at a household furniture sale at Ashby, Leicestershire, The Flashman Papers were discovered. The Flashman Papers are a series of 12 packages of personal memoirs written by Sir Harry late in his life (circa 1900-1910). Wrapped carefully in oilskins, they were found by his family upon his death in 1915 and miraculously not destroyed, but preserved and hidden in a tea chest. Upon their rediscovery, they were claimed by Mr Paget Morrison of Durban, South Africa, Sir Harry’s closest living relative. Mr Paget Morrison enlisted the help of newspaper editor, George MacDonald Fraser, to edit and annotate the papers, the first of which was published in 1969. The publication caused a sensation as history as it was known was rewritten. The hero Gandamak admitted to being, in his own words, “a scoundrel, a liar, a cheat, a thief, a coward and, oh yes, a toady”. History was wrong. Sir Harry, in the course of saving his own skin and despite his better judgement, managed to create the history we know today. Or so George MacDonald Fraser would have us believe. Ironically, while reviewers here in the UK got the joke, in the States, they thought this was a real find, a British hero laying waste to a century and a half of treasured history (see The New York Times, 29th July 1969. This LINK will take you to a copy of the article). MacDonald Fraser has always stated in the books that he has only edited them. This could be a conscience settling thing as Flashy is not the nicest of chaps.

I love historical fiction. Bernard Cornwell‘s Sharpe books got me reading in the first place and my shelves are adorned with almost all of Cornwell’s books, Robert Radcliffe’s Second World War series, Conn Iggulden‘s Ceasar and Khan books and many more. Seeing history through these heroes eyes is wonderfully exciting. MacDonald Fraser took a different tact. Having fought with the Border Regiment in Burma during the Second World War, the author looks at Flashy with an eye very different to how Cornwell viewed Sharpe. Having taken lives himself, MacDonald Fraser knew that it was no small thing and this is reflected in his writing. Flashman shows us the horror of war as it is, mainly because he is as terrified by it as we should be. This offers a remarkable contrast to Richard Sharpe or Jack Aubrey. There are moments in the books that build to the point that, in any other novel, the hero would dive into the breach and save the day. Flashman will wait for the idiot to dive and promptly run in the opposite direction. Which makes for a rather odd reading experience. Our first meeting with Flashy is in Flashman. Having been kicked out of Rugby for drunkenness (See Tom Brown’s School Days), his father purchases him a commission in the Dragoons with a posting to Scotland (following a duel over a courtesan) and a shotgun wedding later, he finds himself in the original invasion of Afghanistan, which went about as well as our more recent one. From the off, MacDonald Fraser shows us that Flashy is a bit of a bastard. In Flashman he rapes a dancer named Narreeman, who later marries an Afghan warlord and tries to castrate Flashman. This, as MacDonald Fraser has admitted, is crass and beyond the pale, but is very effective to show that in Flashy’s world, anything goes. Interestingly, MacDonald Fraser never again had Flashy do anything like this, and had to rebut this incident consistently until his death. His response to Jim Naughty on Radio 4’s Open Book was that this is who Flashman was, he was not a hero and had to be made despicable. Interestingly, given Flashy’s 478 conquests by 1857 (while in a dungeon in Gwalior, to keep himself sane, he counted them all up), probably all the other 477 of them got the better of him, mind you, Narreeman was still hunting him years later on Flashman’s return to Afghanistan. Most books start with him pining after his wife Elspeth from some far British possession he has inadvertently help gain, before his wandering eye catches someone and he ends up up to his neck in trouble. Be it the Taiping Rebellion or standing on the Little Bighorn in full evening dress while the 7th Calvary is massacred around him. Flashy is not a nice chap and he knows it. In fact, in his reminisces he states that he is only after the preservation of his own skin. As Flashy said himself:

data-animation-override>

“It’s a remarkable thing (and I’ve traded on it all my life) that a single redeeming quality in a black sheep wins greater esteem than all the virtues in honest men — especially if the quality is courage. I’m lucky, because while I don’t have it, I look as though I do, and worthy souls like (Kit) Carson and (Lacey) Wootton never suspect that I’m running around with my bowels squirting, ready to decamp, squeal, or betray as occasion demands.”

That statement sums the series of eleven novels and a collection of short stories. Flashman is a bad man. MacDonald Fraser himself stated by the time he finished a book, he hated Flashman and it would take about a year to get over his disgust of the man he had embellished from, in his mind anyway, the true main character of Tom Brown’s Schooldays. MacDonald Fraser says that Thomas Hughes only had Flashman expelled because he was a far more interesting character than Tom Brown. So why am I writing a blog about a dyed in the wool bastard, who’s series of book I haven’t even finished, even though the last book was published a decade ago. Well, it is because they are hilarious and constantly not what you would expect. Only George MacDonald Fraser and John le Carre have me guessing till the final page. The Flashman papers shouldn’t work, but they do. Why haven’t I finished the dozen books? Because I do not want them to end. A Sharpe or Hornblower book follows the usual pattern. Flashy is trying so desperately to get out of whatever he is in, your natural expectations of your hero’s journey are thrown all askew and they are only the more wonderful for it. I remember sitting in the Bricklayer’s Arms in Putney after yet another Fulham defeat and mentioning to my dear departed friend Danny Moss that I was reading Royal Flash, the second Flashman Paper. Danny put down his pint and stated he loved Flashman. We gassed on for the best part of an hour about our virtue-less rouge. It is a memory I will always cherish.

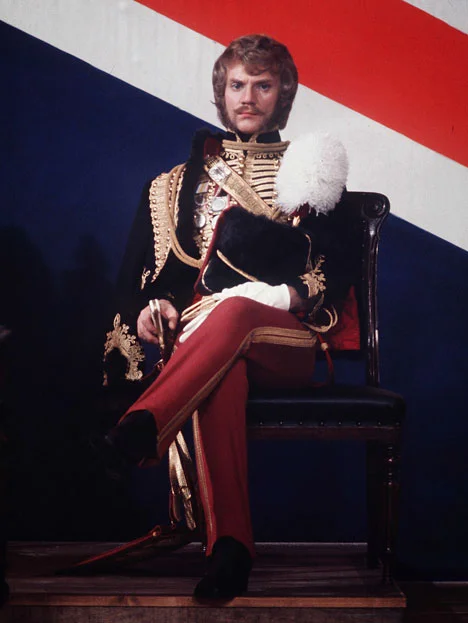

Malcolm McDowell as Flashman – 1975

The books are far more clever than they deserve credit for. Royal Flash for example is basically the plot of Anthony Hope‘s The Prisoner of Zenda. Flashman states that he told Hope the story of his travail in Germany at the hands of Bismarck and Rudi von Sternberg over drinks and Hope stole it. It is a wonderful device and it works a treat. It works so well that the only Flashman film to date is Richard Lester‘s Royal Flash of 1975, staring Malcolm McDowell as Flashy, Oliver Reed as Bismarck and Alan Bates as Rudi von Sternberg. It is not a very good film, George MacDonald Fraser refused to allow another adaptation in his lifetime, but it is notable for a Henry Cooper cameo and an early screen role for Bob Hoskins as a police bobby. Oh, it does have Britt Ekland, which I suppose is a redeeming feature! But, the 70’s had other, better anti-heroes who were not cowards. Oddly enough, it does seem a ripe time for Flashy to grace our screens again. And he may very well do. Sir Ridley Scott, pumping out more films as he gets older, has optioned Flashman and set up a deal at Fox to produce the film. Casting is tricky. Dominic West (of The Wire and The Affair fame) is a huge fan and, a few years ago, would have made a brilliant Flashy. My money is on Dan Stevens, Luke Evans or Jack O’Connell to get the role. Tom Hiddleston would be good, but far too on the nose. The tricky bit is, without the running commentary from Old Flashy, Flashman will not work on the screen and voice over is notoriously difficult to pull off well. Without it though, he’ll, ironically, come off as he actually is, a bastard, which will not make for a good film and miss the spirit of the books. In this humble fan’s mind, have Old Flashy played by Timothy West and young Flashy by Jack O’Connell and you’ll be onto a winner. Don’t believe me? Watch ’71 and see the fear etched on O’Connell’s face. With the true horror of the Retreat from Kabul going on around him with, in the moment of The Last Stand of the 44th, having Old Flashy reminding us that he will happily leave his red coated men on that hill and leg it to Jalalabad, would put an interesting spin on things.

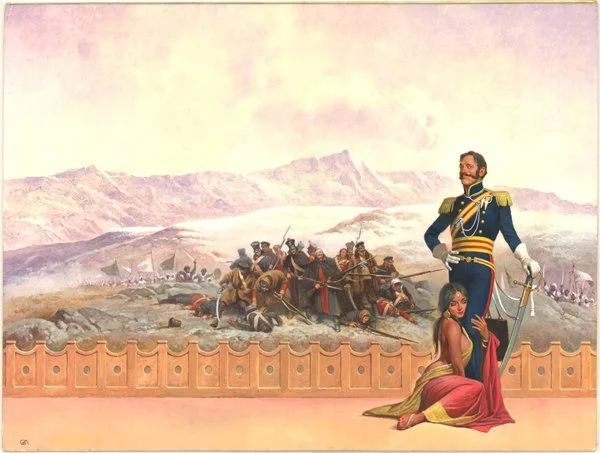

Dominic West in full Flashy fig at the sale of George MacDonald Fraser’s Library.

Harry Flashman is truly one of the great rouges of English literature. A man of no moral character and proud of the fact, the honesty of his actions is rather refreshing. Each book is totally worth the looks of disapproval from your fellow passengers on whatever crowded commuter train when you find yourself laughing guiltily out loud to Flashy telling you:

data-animation-override>

“If ever you have to run slaves – which seems unlikely nowadays, although you never can tell what may happen if we have the Liberals back – the way to do it is by steamboat.”

Flashman is not for everyone, but in his villain, George MacDonald Fraser has created a wonderful chap to travel the Victorian world with. You tut, shake your head and shed tears of laughter along his journey, running away from each historical engagement as fast as his legs will carry him. The thing that is usually missed when talking about these books is George MacDonald Fraser’s wonderful style. Time and again you come across a beautiful passage of prose that seems out of place coming from Flashy mouth. They are wonderful books. But, despite being the despicable scoundrel that he is, Flashy has style is spades, a spade he’ll happily hit you with if it gave him a head start.

Leave a Reply