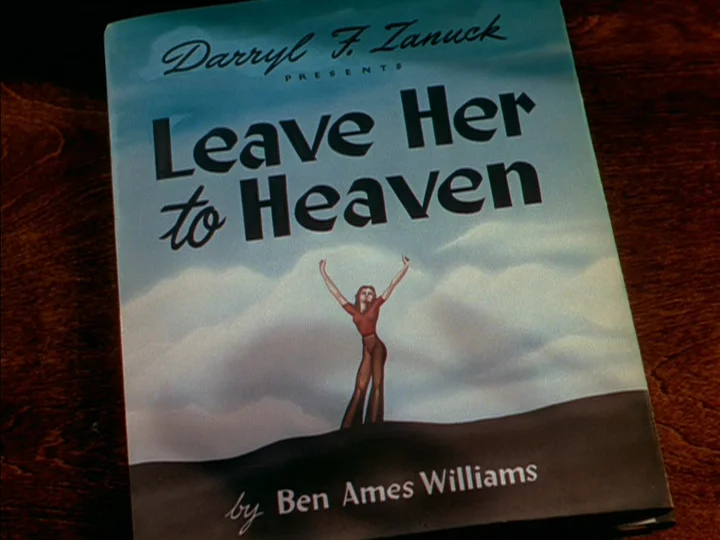

A woman is sat reading a book on a train in one of those sumptuous 1940’s transcontinental train bar-cars. We don’t see the woman’s face, but we see the dust jacket and the picture of the author, the camera pans to a man sat across from her staring at the woman, we recognise the man as the author of the book. The woman lowers the book, incredible, piercing blue eyes radiate over the top of the book. The man is distracted and fumbles about for a cigarette. The woman, amused by this, lowers the book and engages the man she has not yet recognised as the author. But it doesn’t matter, we’re entranced. The actress is Gene Tierney and you cannot look away. Her beauty, those eyes, staring back at Cornel Wilde, the world around you lessens and you wonder what she will do next. Throughout the film, while the camera is on her, she rarely blinks, she holds you with a gaze.

Gene Tierney as Ellen Bernet in Leave Her to Heaven.

You only have to watch the first ten minutes of Leave Her to Heaven to understand why Leon Shamroy won the Oscar for Best Cinematography for this film. He has taken the new form of noir and thrown a bucket of Technicolour over it. He uses deep focus (where everything in the shot is in focus, as opposed to usually just the principle subject) to show everything on the stunning sets. But, at the centre, is Tierney. Tierney’s star was at its zenith in 1945 and would stay there for the next decade. She plays Ellen, a woman who, as her mother tells Cornel Wilde’s besotted author Dick, “always wins”. While at a mutual friend’s ranch in New Mexico, Dick is almost fobbed off by the rest of the guests and Ellen’s family, practically shovelling him to Ellen as they already understand the inevitability of what is about to happen. They are thrust together by the sheer force of Ellen’s will and Daddy issues. Her mother and adopted sister (Mary Phillips and Jeanne Cain, respectively) watch on with a resigned understanding of what is happening. The rest of the cast are almost afraid of getting in Ellen’s way. In most films, this would not work, but Wilde’s engaging bewilderment and Tierney’s sheer charm is compelling. You start willing them together, especially when Ellen’s fiance shows up and it is Vincent Price in very stuffed shirt mode. Price and Tierney had worked together just the year before in Otto Preminger’s equally incredible Laura, where Price had played Tierney’s titular Laura’s fiance. So the audience already felt that they knew their history. It is a clever trick that the studio system used time and again.

Needless to say, Ellen wins her man and slowly her obsessive compulsions mean that she cannot share Dick with anyone, not her family, not Dick’s disabled brother Peter, nor their unborn child. Looking back on this film with 21st-century eyes, the depiction of Ellen’s mental health is a worry, but it was also a staple of the Golden Age of Hollywood. The obsessive as centrepiece to plot. Ellen’s compulsion leads to murder and even framing her sister for murder. I won’t tell you whose. The film has two of the great Hollywood Noir set pieces. The rowboat scene, with Tierney’s steel-blue eyes hidden behind sunglasses while she rows behind the swimming Peter. And then later, the fall down the stairs, where she is dressed in shimmering cold blue satin, matching the mood of her heart towards her unborn child. The costumes by Kay Nelson are incredible, considering she was clearly trying to top the outfits that were painted on Tierney in Laura. Nelson’s wardrobe does an incredible job, causing us trouble in rectifying the beauty on screen with the coldness of Ellen’s heart.

On the water. The row boat scene.

Watching Leave Her to Heaven now, it still has the same effect as it did on me thirty years ago. I remember watching it with my Grandmother (we watched the black and white version, it was years before I saw the Technicolour print), being transfixed by Tierney and struggling to reconcile Ellen’s actions with Tierney’s beauty. Which is exactly what the film was designed to do. Now, knowing so much more about Tierney, I watch this film with sadness. Ellen’s character is clearly ill and in the years to come, Tierney would lose her own battles, especially with mental illness. While pregnant in 1943, she worked her only shift at Bette Davis’ Hollywood Canteen, where stars fed and watered servicemen and women who were in LA. The stars were doing their bit for the war effort and it was incredible PR for the studios. On the night in question, a female Marine broke a base quarantine for German Measles to see Tierney. She met her idol, hold her what she had done and left. Tierney fell ill and later her daughter Daria was born deaf, blind and with serious mental impairments. Daria would spend her life institutionalised. Agatha Christie would use the sad story for The Mirror Crack’d Side to Side. Tierney’s beauty would mean that she would be seen on the arm of some of the greatest men of the age like Howard Hughes. She had an affair with John F Kennedy, but she kicked him to the curb when it became clear he would never marry a divorcee. Next came Prince Ally Khan, fresh from Rita Hayworth, and then she met oil baron W Howard Lee who she would remain married to for the rest of his life. In 1955, tens years after making Leave Her to Heaven, while filming the very odd Cinemascope epic The Left Hand of God, Humphrey Bogart started to notice Tierney’s behaviour, which mirrored that of his sister, who had her own battles with mental illness. Bogey helped Tierney through production (Tierney’s not at her best in the film but her scenes with Bogart are very lovely, very tender) and encouraged her to seek help. She checked herself into a clinic and underwent electroshock treatment 27 times. If anything, this made things worse.

Tierney and Cornel Wilde

Watching Tierney as Ellen is mesmerising. In knowing the heartbreak and the illness she fought adds greater depth to a rather stunning performance. The run of films Tierney had from 1943-1947 is the envy of any actor: Heaven Can Wait, Laura, Leave Her to Heaven, The Razor’s Edge and The Ghost and Mrs Muir. Tierney’s talent outshone her beauty. She is responsible, with Barbara Stanwyck, for creating the Femme Fatale. She famously didn’t need to wear stage makeup, her skin was so perfect. She happily put some the most powerful men of her age in their place when they didn’t measure up and she fought, tooth and nail, with her own demons. That she is somewhat forgotten now is heartbreaking to me. Especially when you watch Leave Her to Heaven. It is a commanding performance and one that should never be forgotten.

To learn more about Gene Tierney, I highly recommend Karina Longworth’s You Must Remember This, podcast episode Star Wars Ep IV: Gene Tierney (or the many loves of Howard Hughes, chapter 5).

You can also read the lovely Nitrate Diva’s blog about Leave Her to Heaven, it is probably a better read than the above!

One final recommendation is this clip of Martin Scorsese introducing the remaster of Leave Her to Heaven. Scorsese is always engaging.

Leave a Reply