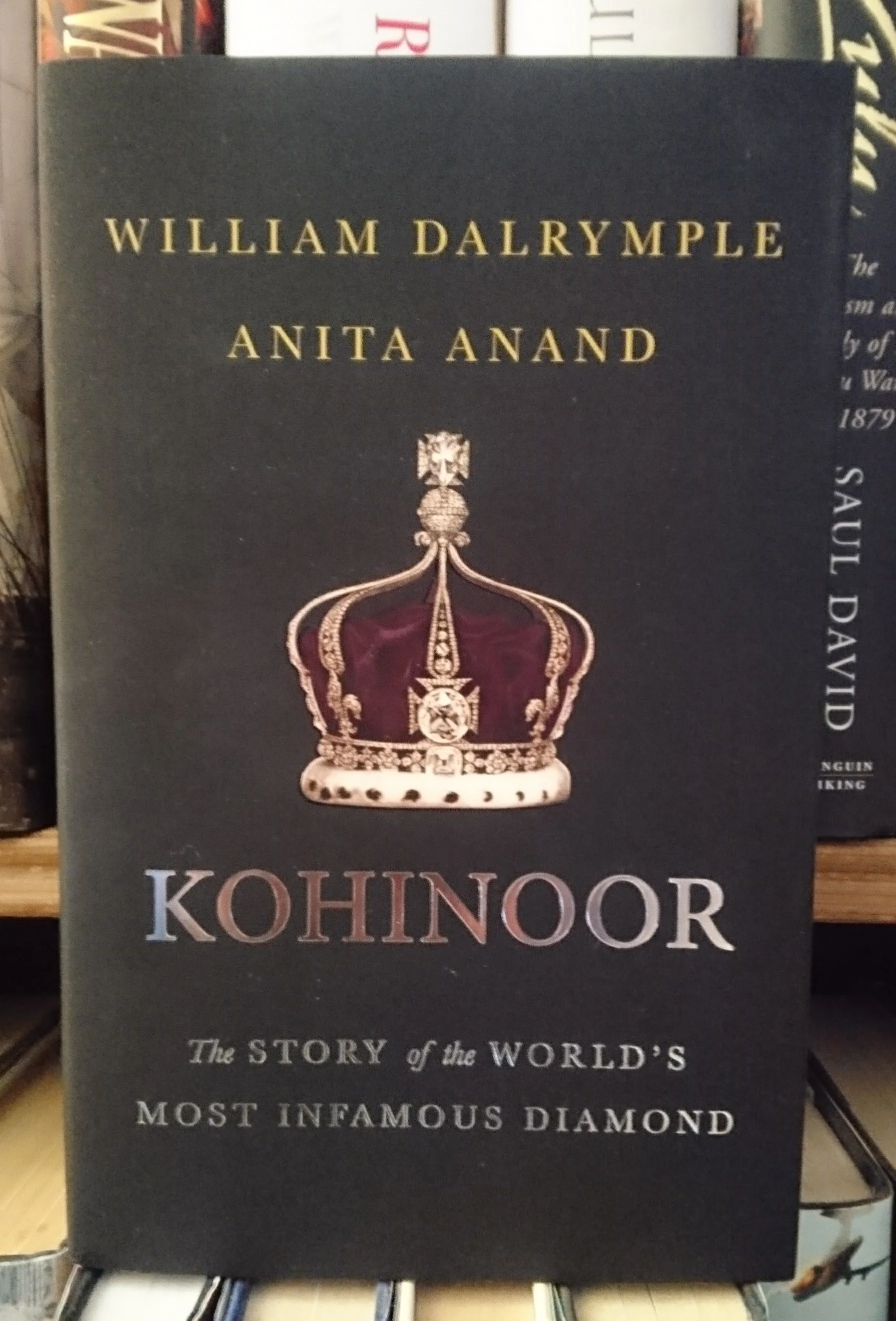

I remember a few years ago taking my daughter to the Tower of London and we visited the Jewel House. On the train on the way up, I’d regaled her with tales of the Koh-i-noor diamond. Granted, much of the “colour” of the tale was flavoured by George MacDonald Fraser’s telling of how the diamond ended up in Queen Victoria’s hand by way of his rouge Harry Flashman (and the historical note at the end of Flashman and the Mountain of Light). As we gazed at the rock in the centre of the Queen Mother’s Crown, my daughter thought it beautiful, if smaller than she thought it would be. Which is part of the tale of the diamond and how western desire and tastes forever changed the Mountain of Light and is wonderfully told by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand. Dalrymple is what might have once been called an “Old India Hand”, writing extensively on the country with incredible colour and Anand, an Anglo-Punjabi journalist, who has written about the last Indian holder of the Koh-i-noor’s granddaughter, join forces to describe the incredible history of this literally blood soaked diamond. Kohinoor is split evenly between them, with Dalrymple investigating the more ancient history of the stone and Anand tracing it’s history in the last 300 years. The split brings a very interesting slant to proceedings, in which the British involvement and lust for the diamond is recounted, as is should be, by one of Indian descent.

Dalrymple’s journey through the past, recounting the takes of the large diamonds that have been recorded throughout the history of the sub-continent, is wonderful and a timely reminder that the world’s history is not based around what happened in the west (See Peter Frankopan’s brilliant The Silk Roads for this in detail). Dalrymple is mostly spinning tales and legends because the exact history of the Koh-i-noor was never recorded. Before sending the stone to Britain, the Governor-General, Lord Dalhousie, ordered the history of the stone to be recorded. An East India Company magistrate, Theo Metcalfe, was given the task of recording what was known about the diamond. Metcalfe, frankly, gathered rumour and stories, wrote it up to sound good and sent it off. He seems the very epitome of the chancing civil servant. Unfortunately, what Metcalfe wrote became the accepted history of the Koh-i-noor, the fact there is no basis in fact didn’t seem to bother anyone too much. Which is where this book does such a fascinating job. The tale covers three dynasties, the Mugal, the Durrani and finally the Sikh, before it’s journey to London. That the diamond was held by rulers in what is now Pakistan, Afghanistan and India, not only shows the breadth and power of the sub-continent in the years before European meddling, but also why this diamond still raises such passion and debate. The end of Part One deals with the frankly incredible Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh who wore the Koh-i-noor on his arm and ruled over much of the western part of the sub-continent. The intrigues of his palace make for wonderful reading, coloured by eyewitness accounts by the Europeans who worked for or passed through in Ranjit Singh’s court. With his death, his empire fractured and the waiting John Company pounced. Part Two, which is written by Anand, deals with the overt British meddling in the history of the Koh-i-noor.

Anand’s touch throughout the journey post Ranjit Singh is sympathetic but firm. She doesn’t shy away from the darker side of the power-politics in the 18th and 19th century, which was usually at the point of a blade and musket. The Anglo-Sikh Wars that brought Ranjit Singh’s empire to it knees are the stuff that the world is still facing up too today, as once they were completed, the East India Company controlled India. Throughout this, the widow of Ranjit Singh, the indefatigable daughter of Ranjit Singh’s kennel keeper, Rani Jindan stands above the men of tale. Her son, the last Maharaja, Duleep Singh, would be end of the sad tale of the Koh-i-noor, but his mother was an incredible woman, keeping her son alive, manoeuvring him onto his father’s throne and then ruling as Maharani in his name. But even she couldn’t stop the rise of the British and this is where Anand’s class comes through. The final act of the Koh-i-noor’s journey to London is basically the stealing of a Boy’s crown and the banishing of his mother and Anand tells it brilliantly. The other interest bit is how the story of the Koh-i-noor becomes rather dull when the diamond leaves it’s home shores. In England it is disparaged and finally recut to about half of her original size, to meet the tastes of people who lusted after, but never understood, the diamond they now posessed. The slow fall of Duleep Singh in Queen Victoria’s court is heartbreaking, which gazing upon the Koh-i-noor now, is too.

Dalrymple and Anand have written a terrific biography of a greatly misunderstood and divisive item. The Koh-i-noor is fought over to this day and is used as a rally cry for nationalists half a world apart. That such an even handed tale has been written by two authors is testament to their skill and, in no small part, to the incredible stone that sits in another country’s secondary crown in a vault in East London. Kohinoor is a brilliant race through the history of the sub-continent, all the rough the lens of the Mountain of Light.

Kohinoor is published in India by Juggernaut and is out now. It is published in the UK by Bloomsbury and will be released on 15th June 2017.

The Koh-i-noor in the Queen Mother’s Crown as the Queen Mother laid in state, April 2002.

Leave a Reply