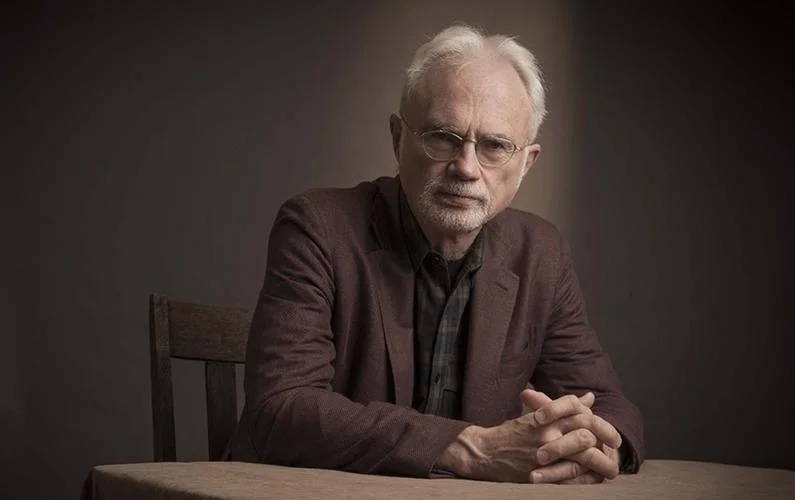

John Adams, composer of Scheherazade.2

A strong young woman stands before dour old men. They are arranged around her, there faces drawn with disdain, their beards long and grey. The young woman stands accused of overstepping the bounds of where they feel a woman should remain. They hurl accusations at her, she stands strong, replying calmly. They try again, voices raising louder with each attempt to get the woman to submit, each time she turns their arguments back at them. The men with beards attack again, trying to twist her words against her, she retorts and again they redouble their efforts, this time, eliciting a reaction where Scheherazade responds with passion. And as this extraordinary scene plays out before you, not a word is spoken.

On Thursday last (8th December 2016) I had the privilege of attending the London Symphony Orchestra with John Adams conducting his dramatic symphony for solo violin, Scheherazde.2. The added bonus was the young lady that the symphony was written for, violinist Leila Josefowicz, was our soloist. Scheherazde.2 takes it’s inspiration from the Scheherazade of the One thousand and One Nights fame. To save her life, she beguiles the King with a story a night, never quite finishing the tales as the dawn breaks and the king, eager for another story, spares her. For a thousand nights, Scheherazde’s tales fascinate the king as he slowly falls for her. On the morning after the thousand nights, the king spares her and make her his queen. In John Adams’ mind, a modern Scheherazade would face incredible dangers against powerful, blinkered men, just as the king was. Watching the events of the Arab Spring, Adams saw women standing tall and sometimes paying the ultimate price for their valour. Adams saw a woman, in love, standing up for what she felt is true in the face of the perceived norms of her society. She has a night of passion before being dragged before the Men with Beards, as described in the opening. She the escapes from the from them flies to freedom and a sanctuary of her own choosing. In four stunning movements, Adams creates a powerful narrative, but that narrative is only as realistic as his Scheherazde.

Leila Josefowicz

Leila Josefowicz inhabits Scheherazde, which is only right considering the piece was written for her. Josefowicz can move from great subtlety to incredible power and rage in the blink of an eye. Having listened to the recording of Scheherazde.2 quiet a bit (St. Louis Symphony conducted by David Robertson with Leila Josefowicz on Nonesuch Recordings), you can feel the emotion and energy in the performance. But seeing Josefowicz perform, from about twelve feet away, you get so much more. Josefowicz doesn’t so much as play the part of Scheherazde with her instrument, she lives it. She prowls the stage when the part calls for it and yet seems to shrink into the subtler elements of the score. During the 3rd movement, Scheherazade and the Men with Beards, I was transfixed by Josefowicz. Arrayed around her, the LSO harried and sparred with her and tried to break her down but she got taller, louder, prouder. The way Adams harnessed the LSO and allowed Josefowicz to seem isolated out front was brave and showed the intimacy and confidence of conductor, orchestra and soloist.

I owe my love of classic music to a pianist who, before we used to play baseball in his back yard, would hammer out some Chopin on his baby grand. More than once, I’d just sit there and listen as the afternoon faded away. One trip back to Canada, I blew out spending time with my Grandparents to go and see Anne-Sophie Mutter with him. It was life affirming. Not since then have I been to a performance where I felt alone with the music. Thursday night’s performance was raw and exposed and beautiful. In Leila Josefowicz, we have an artist that is shining so beautifully and creatively that she was a true, pure joy, to behold. Until next time then, Leila.

John Adams and Leila Josefowicz at the premier performance of Scheherazade.2 in New York, 2015.

Leave a Reply