We live in a world where our focus is constantly drawn East. We see terrible things happen, our leaders contemplate doing terrible things and dropping equally terrible things in response. We look at what we call the Middle East as a modern problem, as if our focus has only recently turned to it. But, living in the West we forget that everything has come from the East. While Rome was falling, the East was flourishing. Before we worried about oil and gas, we sent gold and silver East for silks and knowledge. We owe everything to the East. And yet, with our minds firmly on our own importance, we tend to think of it as a dusty backwater. The Silk Road, to modern minds, is a website on that bit of the internet you can’t find when you pop it into Google. Yet, The Silk Roads made the world what it is and still are the arteries of everything we know and everything that defines power in this 21st Century. But, what is a “Silk Road” and why is it still important? Equally importantly, where do you start. Peter Frankopan decided to start at the beginning and he has written an enthralling account of this weighty subject in an equally weighty book. While The Silk Roads may break your foot should you drop it, it is well worth the risk.

Frankopan is a Senior Research Fellow at Worcester College, Oxford and the Director of the Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research. When a book opens with the line “From the beginning of time…” you know where you stand, and yet from this jumping off point, you never feel lost. Frankopan knows his subject but, wisely, considering the incredible scope of the history he is tackling, he keeps the narrative rolling, focusing on pivotal moments in the development of the trade routes and the conquests of them. While the focus on a time period and subject may seem surprising and others are mentioned in passing (the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin in 1187 is covered in a paragraph and a half), the developing theme of the tale is constantly evolving and expanding. While empires rise and fall, each chapter follows it’s title, overlapping in time frame with the next, with the foundation continuing to build and the story of the development of the world goes on in a way that keeps you engaged and on track. What is interesting is that while the focus of our eyes on the region is usually one of the religious tensions that arises from the three monotheisms that grew out of the region (for more on this, see Tom Holland‘s wonderful In The Shadow of the Sword), commerce is the god that truly rules these roads. While the religious aspects of the region, the Crusades and the dying of the old gods are underlying most of the tale, the most striking aspect is the way that, while the political influence moves West as the story progresses, the money continually flows east. This is most striking in the chapters “The Road of Gold” and “The Road of Silver”. Covering the expansion of Spain, Portugal and eventually England, the way the new continent of America is opened up, its people killed and enslaved and its resources packaged up and sent home. Once in Europe, the gold, silver, pearls and other fineries are promptly shipped East for the trinkets that the “Civilised” world desires. The boom and bust of gold and silver prices and the fluctuations of the trade are so very familiar to us today and you sometimes forget you have only reached the 16th century in the tale.

As you would expect, the second half of the book is taken up on more recent history. With the rise and commercialisation of England, not just trading with but taking a large section of the East, the development and influence of the sea lanes to China have a profound affect on the central region of Asia. This in turn leads to our more common discussions about oil and this to the politics of men in clubs and offices, carving up a part of the world they could never hope to understand or control. While our geopolitics of today may seem like a problem we made ourselves, the seeds were planted hundreds of years ago, the sprouts of which flourished in those heady days before the First World War. Coupled to this, reading the tales of short-termism in political thinking in the inter and post-war periods, you find yourself uneasy at seeing the genesis of the issues our leaders feel compelled to act upon today.

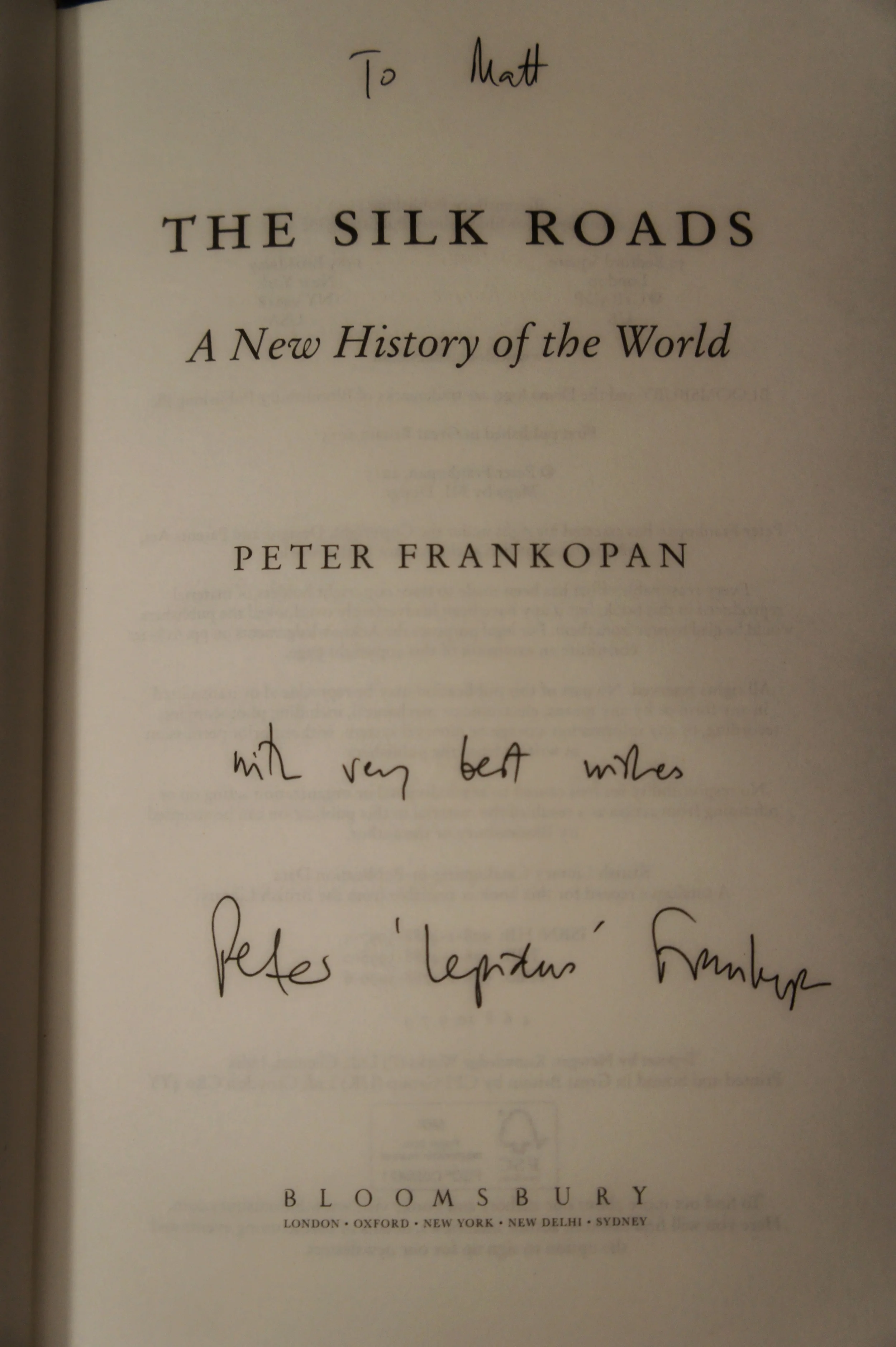

Frankopan’s use of language is wonderful and his use of eastern sources so refreshing when we are used to seeing other people’s history through western eyes. He does enjoy using the phrases “modern scholars” and “the latest research” rather a lot but this is a minor quibble when what appears to be a daunting undertaking is such a joy to read. Narrative history is tricky to get right and William Dalrymple, in his review of Tom Holland’s Dynasty and Mary Beard’s SPQR in the New Statesman, rightly stated we have a triumvirate of classical narrative historians of the very highest calibre at the moment. Frankopan is “no weak Lepidus” indeed and I thoroughly enjoyed the brief chat I had with him at a talk he hosted at Daunt Books with Tom Holland. The tale Frankopan weaves is as delightful as the design of the book itself, while offering a sobering and sometimes terrifying vision of the past repeating itself. Its rare that a book so timely has landed as aptly as this, as our gaze once more focuses East, it is worth every step on Frankopan’s Silk Roads.

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan is available now, published by Bloomsbury. Peter Frankopan is on the Twitter machine as @PeterFrankopan.

Leave a Reply