Chris Beckett

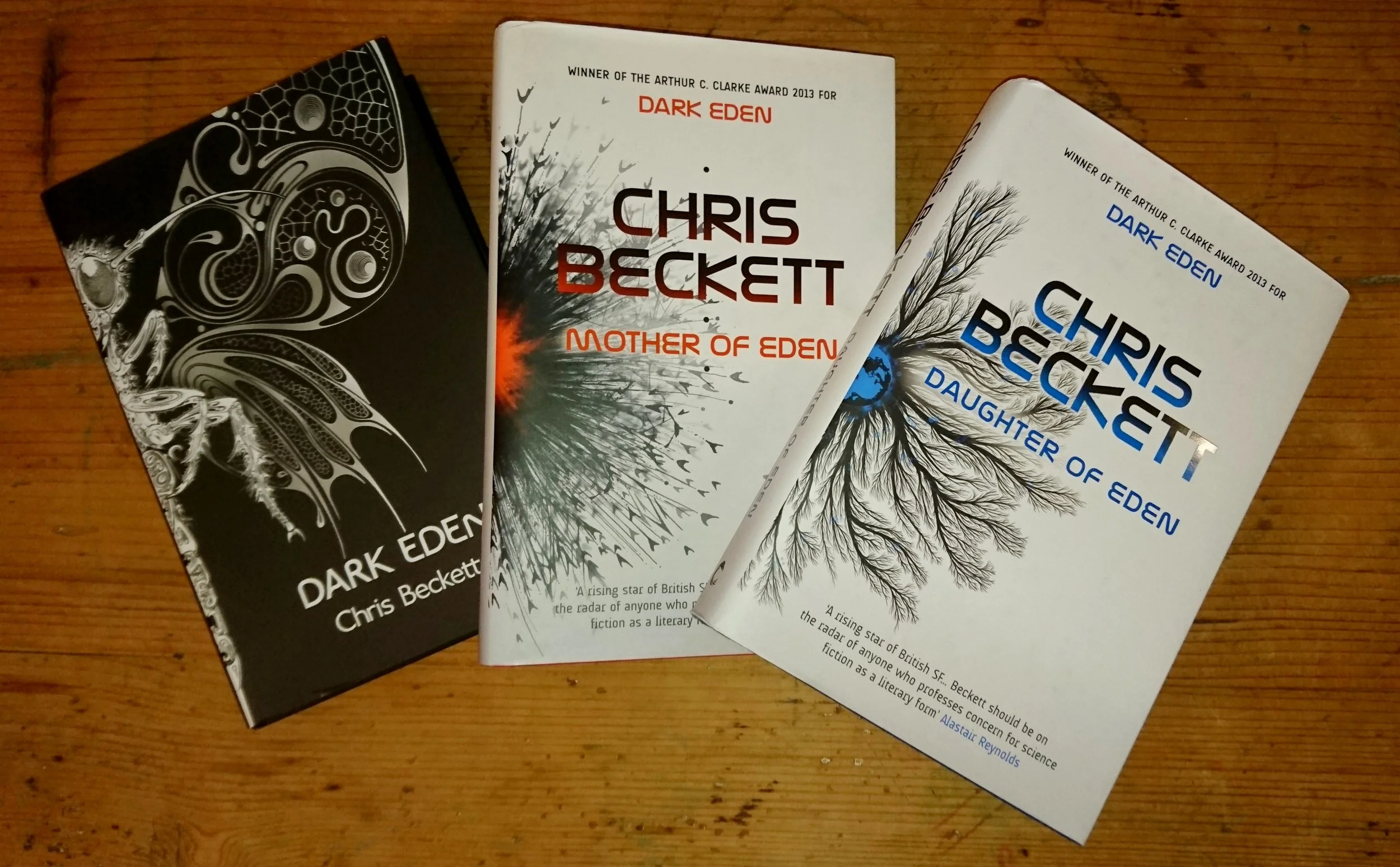

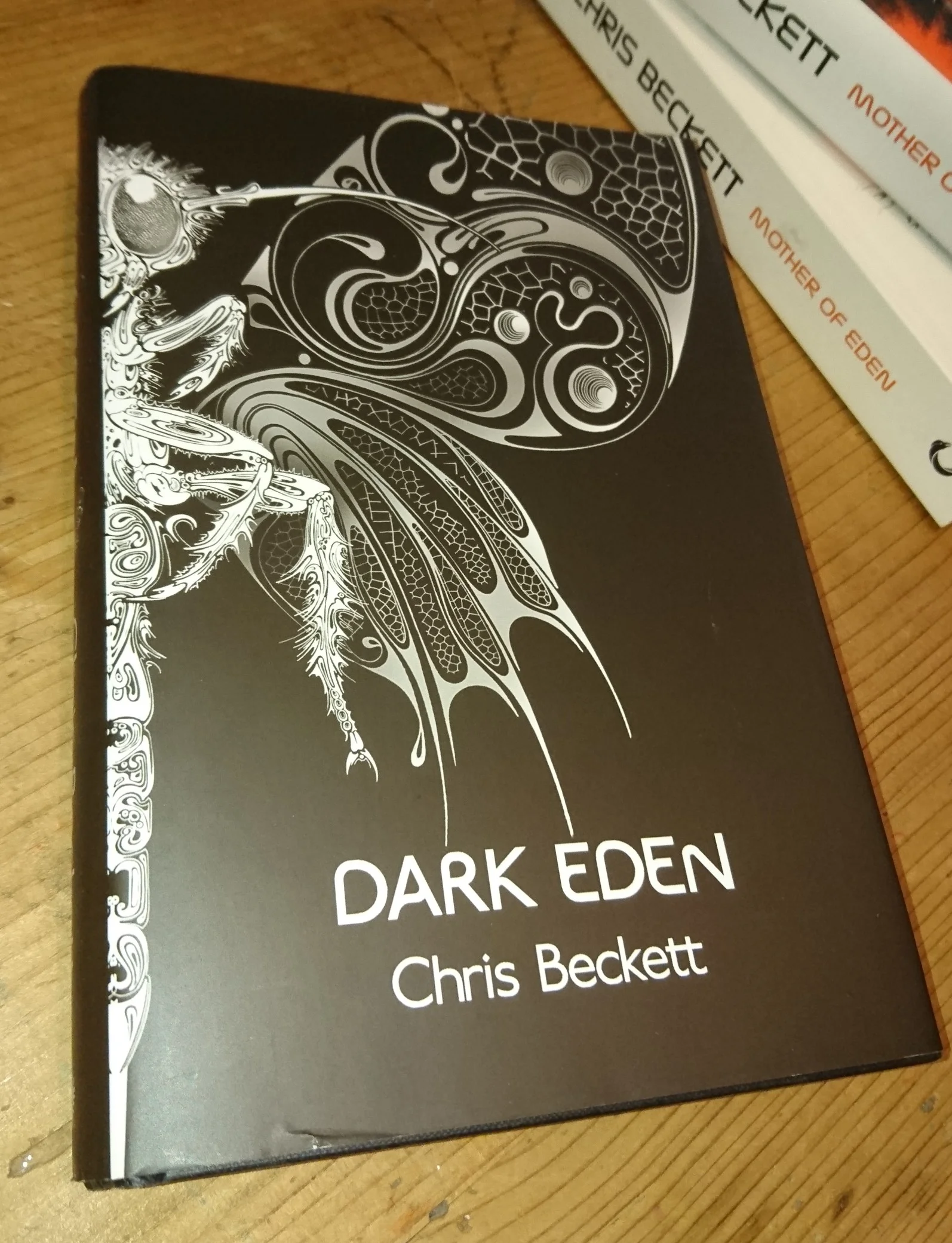

When I first reviewed Dark Eden by Chris Beckett back in June of 2014, I mentioned I had bought it on a whim. In all honesty, the cover design (by Si Scott) was so striking that I would have bought it for that alone. Judging Dark Eden by it’s cover, thankfully, proved to be a wonderful choice. The world named Eden by Tommy and Angela is a truly incredible creation by Chris Beckett. The planet with no sun that generates it’s own heat, air and light is captivating. The Family that live there, the descendants of Tommy and Angela, wait patiently for Earth to return and save them. Only thing is, generations have passed and some of the younger folk are getting itchy feet. Over the course of the Eden Trilogy, Beckett explores their desire for more and the basis of truth and power. The tale is told in an evolving English that had devolved to babish speak in the first book and becomes more complex over the 400 years that the following two novels, Mother of Eden and Daughter of Eden, cover the aftermath of the family split.

Needless to say, I was enthralled by the novels. While I was worried about the jump forward between the first and second books, as I’d become attached to the group in the first (and fearing change as I do), I’d need not have been. The skill of Beckett is in his ability to challenge the reader as much as his characters. The development of not only of the language, but of the belief system that the expanded Family created, is fascinating and has evolved from the tale we know from the first book. The Eden Trilogy is a towering achievement which I cannot recommend enough to all. Through the glories of Twitter, Chris very kindly agreed to answer a bunch of my Eden and creative based questions.

I hope you enjoy the discussion.

Matt Bone – How did the original idea for Eden come about? Did the idea for the planet come first or was it the situation?

Chris Beckett – I came up with the idea of the planet Eden initially for a short story called The Circle of Stones which was published in 1992. Central to the story was the act of transgression which the title refers to and which I also used in the novel, the idea of an act that was quite spiteful and cruel, and yet perhaps necessary all the same. I don’t remember the exact moment when I decided to make this happen on a sunless planet, but my theory is that it came to me as I sat in front of my old Amstrad computer which had luminous green letters on a black screen, a bit like glowing trees in a forest, and also an inversion of the normal arrangement of black letters on a light screen, rather in the way that Eden is an inversion of Earth. Anyway, once the idea came to me, it opened up all kinds of possibilities!

MB – As I’ve mentioned it in most of my reviews of the books, have you seen the Twilight Zone episode “Probe 7, Over and Out” about an astronaut (Adam) and woman (Eve) being stranded on a strange planet, called Earth?

CB – No I haven’t. I’ve heard it said many times that there are loads of ‘Adam and Eve in Space’ stories out there -even that’s it’s such a hoary old theme that it has long since been done to death- but I can only think of one instance that I’ve actually read, and that was Perelandra by C S Lewis (aka Voyage to Venus). Not a major influence on my books, as far as I know, though it contains some truly gorgeous world-building.

MB – I’ve always been a huge fan of Philip K Dick’s incidental approach to world building. In The Man in the High Castle and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the world just is and the journey through it is what informs the reader, something that the TV show and Blade Runner took on-board too. As a writer, especially with Dark Eden where the world was the norm for John, Tina and Jeff, how did you approach the task of description and not over-egging the pudding with exposition and losing the wonder?

CB – Yes, I like the way Dick never stops and explains things. I think the imagined world should, as far as possible, just emerge as the reader journeys through it with the characters. The Eden books imposed a certain discipline on me in that respect, since all of them are told entirely by people who live in Eden. There is no external narrator to comment and explain things, and if my narrators explain things too much, it will just sound forced (as if a character in a contemporary novel were suddenly to explain how a car works or what a mobile phone is). The secret is to insert information in small parcels, These can be a little bigger than is strictly realistic (John does actually explain quite a lot about those trees, for instance), but they mustn’t be so big as to jar on the reader by slowing down the action. With enough small parcels the reader can assemble the world for himself/herself. One challenge, I found, was that my supply of metaphors and similes was seriously restricted, because the characters could only compare things to other things they knew. However I think in some ways that worked to my advantage in the long run, in that the reader is never drawn out of the world of Eden.

MB – The use of language across the three books is brilliant, especially the way it evolves over the course of the 400 years you cover. Can you explain your thoughts about deconstructing English in the way you did and how it would “grow up” in the period between Dark Eden and Mother of Eden?

CB – I relied on gut instinct for this mainly, but I had the idea that, in the first generation on Eden, there would have been a period when there were only two parents and their children. I thought in this context, with no other adults around, language would become more childish. Little children repeat adjectives for emphasis, for instance. I also had the idea that in a rather simple culture which is basically oral language (they have writing, but they only use it in a limited way and most people can’t read) would take on a slower and more musical quality. In my head they linger over those repeated words -bi-i-i-ig big- and there’s a kind of lilt to the way they are spoken.

In the much more sophisticated society that had evolved by the time of Mother of Eden, language would be becoming more complex again. (In reality it would presumably become complex in ways that diverged even more from standard English, like modern French evolving from pidgin Latin). It would also start to vary from place to the place, particularly between the two continents which have been developing in isolation to one another: Mainground and New Earth. I didn’t attempt a completely realistic representation of this but tried to give a sense of it.

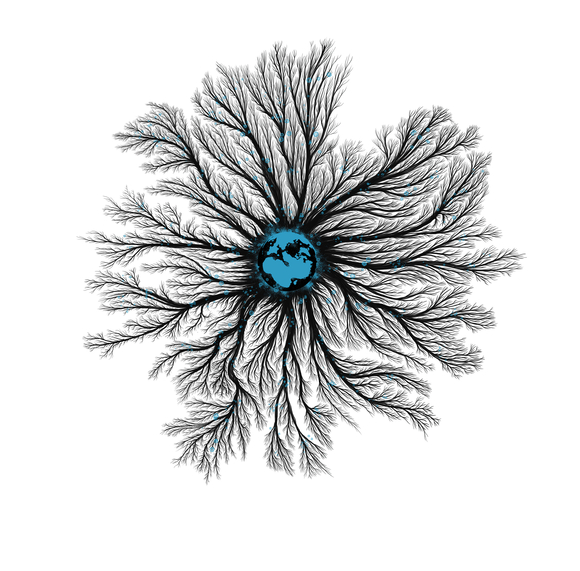

Art by Chris Thornley for Daughter of Eden. www.raid71.com

MB – The way you approached the development of the language, in Mother of Eden and Daughter of Eden especially, Starlight and Angie both, at various times, explain the differences in the way Batfaces (those born with a cleft lip and/or palate) and the various people of Eden speak, by describing it phonetically. What was your decision process about not writing totally “in dialect”? Was this for accessibility or just for your own sanity?

CB – My own sanity. And readability. I think it could be tiresome for a project on this scale to have everything written out phonetically.. It can be done though, as in Russell Hoban’s wonderful Riddeley Walker (which was certainly an influence on this book).

MB – The evolution of the stories that The Family hold so dear is a central theme in the novels. What is your view on belief and faith, considering the age of the tales the major religions are based upon?

CB – I was struck by the idea that many of the stories in the Bible are actually about quite small domestic events, or very local political conflicts, which have grown and mutated to mythic proportions. We humans are always mythologising things, even now, imbuing them with magic, and in the process changing them.

I don’t subscribe to any religion, but I completely get the need for stories which allow us to feel part of a greater narrative. These stories are never really ‘true’ and yet, for some people, they provide access to a well of truth that otherwise they might not be able to reach. (I say for some people, but actually I suspect that this is true of all of us, though the stories of non-religious folk are less obviously mythical).

At the same time, religions are always, so to speak, contaminated by power. Someone gets to tell the story, someone gets to say which story is ‘true’ and which isn’t, and those ‘someones’ tell the story in a way that suits them and legitimates their position. So a religion is at the same time a source of comfort, an access point to truth, and a piece of political propaganda. I’ve tried to explore this in the Eden books.

MB – Mary the Shadowspeaker is a fascinating character. She seems a very pragmatic priestess, yet one who truly believes what she has chosen too. What are your views on that flexible commitment to belief and the approach you leave Angie and Mary taking where they pick and chose the stories to tell?

CB – When I talk to people who subscribe to a religious belief, I’m always struck by how pragmatic they really are. ‘Belief’ in that sense is a much more complex, negotiated, thing than, say, my belief that the sun will rise tomorrow morning. People often flip -and indeed whole religions often flip- between literal and metaphorical interpretations of stories, and they also mix and match: many devout Catholics use the pill, for instance. So, while they have a strong allegiance to certain basic building blocks, they actually use those blocks to construct their personal version of the narrative in quite a flexible way. Two Christians can sit next to each other in a church and happily participate in the same liturgy, and yet have quite radically different ideas about what it all means, which are both also different from the view of the priest conducting the service. I’ve noticed too that religious people are often happy to live with contradictions in their beliefs, and not worry too much about trying to resolve them all. I think this flexibility, combined with a degree of rigidity about outward forms, is one of the reasons that religion is so durable and so useful as a way of bringing people together. I think Angie and Mary, in their different ways, recognise this, but their personalities are very different. The story Mary likes to tell herself is that she knows what’s what, while Angie is more humble.

MB – The pragmatism of those with a religious belief (as one of Jehovah’s Witnesses myself) is a concept I see and find personally fascinating. As one who does not subscribe, do you feel that the pragmatism lessens the structures of a faith itself? Or does the sometimes dangerous bonds of belief, in your view, become more import than the “faith” itself?

CB – If I get what you’re saying, this is a question which I simply could not answer in a few lines. I think my book The Holy Machine contains an effort on my part to explore to some of the kinds of questions you are raising.

MB – The shift from a matriarchy to a patriarchy with the increase in violence in Dark Eden was very interesting, especially contrasted with Starlight’s journey in Mother of Eden. Do you feel that that shift is inevitable or that an increasing society will enviably lean towards violence and a male dominated hierarchy?

CB – My idea was that, at the beginning, Gela was the stronger and more mature human being, while Tommy was immature and narcissistic. She therefore became the dominant figure in the family, and established a tradition that continued. Even in our world, I think, women are usually dominant within the family. My idea was that, when there ceased to be just one family, and competing groups emerged, men began to get more of an edge, if only because men on average are larger and physically stronger than women.

There is always a potential for violence, it seems to me, when there are competing groups of people who can see themselves as ‘them and us’. I’m not blaming this on men, but it’s a fact that would have given men an advantage.

One or two reviewers criticised Dark Eden for its apparent message that patriarchy is inevitable. My actual view (as expressed by Tina right there in the book) is that patriarchy is inevitable AT A CERTAIN HISTORICAL STAGE. The history of Earth surely supports that. It can’t just be a coincidence that every society on Earth, whether in the New World or the Old, has been more or less patriarchal for as far back as history records. But, having said that, I do NOT think that patriarchy is inevitable for all time. We are already seeing women playing all kinds of roles that would have been unthinkable a couple of generations ago. (I had a great aunt who was a university professor. When she was a student herself, women weren’t even allowed to receive a proper degree!) Physical strength is much less important as a determinant of power now, and women are able to take control of their own bodies in a way that is unprecedented in history. (I referred to the pill previously: I suspect that reliable contraception may be the most transformative of all the new technologies of the scientific age.)

MB – Throughout patriarchal societies, though, we still see strong, powerful women making the system work for them. In our history we have Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians (Note to Readers: if you’ve never heard of Aethelfaed, shame on you and here is a link to historian Tom Holland to give you a glimpse of an incredible woman), an example I try to call to mind as often as possible. On Eden we have Tina, Starlight and Mary, smart women using their brains to influence the world they inhabit. Do you think that Eden, when we leave, it is at a point where intelligence is starting to exert itself over brawn? Granted, we here are not there yet, but it would be a nice thought. I also loved that Tommy, the quintessential “Hero Astronaut” was not the best possible example of someone being sent into that situation. Something Michael Lewis covered very well in Moneyball.

CB – More very big questions, not easy to answer in a few lines. Actually, from the beginning on Eden, intelligence has probably been more important than brawn. (John Redlantern was a smart guy.) As society becomes more complex, though, it does create roles which offer more scope for bright people than would have been the case before. You have skilled roles like metalworkers and boat-builders, but also roles like those of the Teachers in New Earth, or the Shadowspeakers in the Davidfolk Ground, who are sort of the intellectuals of Eden, the people who tell and retell the stories which make society function. As these kinds of role become more important, clearly there is more scope, as you say, for strong, powerful women to make the system work for them. But Eden (like Earth) has a long way to go.

MB – We’ve spoken on Twitter in the past about renewable and clean energy sources. New Earth finds the green ore that allows them to create metal. With that comes pollution and oppression, yet they have learning, in a way. Whereas on Mainground, while sticking to tradition, we have overhunting and a level of stagnation. What was your thinking in displaying the issues faced by both sides displaying a naive respect for their environment and future?

CB – In the original Genesis story, God tells living things to ‘be fruitful and multiply’. When the human population is small and the world it lives in is large, it must be very hard to believe that in the long-run humans could despoil an entire planet. Even if that were to be recognised as a theoretical possibility, it would be seen as a problem for the future not for now.

It seems to me that ‘progress’ of any kind does in the long-run come with a price tag, to the point that, with the benefit of hindsight, we might even wonder if the price was worth paying. (A couple of months ago, I read Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari, which is very good on this). Even in Dark Eden, John’s rebellion brings new possibilities at a huge cost, and in future generations, half of Eden considers that cost to have been too high.)

MB – Do you think we can be blinded by the hopes of progress or do you think the discussions, like are currently ongoing about gene editing and manipulation for example, a positive sign of humans trying to understand the impacts of this technology before rushing ahead?

CB – I’m not a great optimist about progress. I’m not sure that the human race is necessarily much happier or wiser now than it was ten thousand years ago (though obviously I hope so), just better at manipulating the material world. Seems to me a lot of apparent progress creates as many problems as it solves, and I think people are right to be cautious. Conversely, areas where we really do need new technology (such as green energy and energy storage) seem to progress unnecessarily slowly.

MB – The environment and native animals of Eden are truly wonderful. I think, after the language of the tales, the animals and fauna are the most striking elements your trilogy. How did you visualise the creatures to enable such vivid descriptions?

CB – I think SF writers are often either a bit lazy or a bit random, when describing animals and plants. Rather than just come up with super-weird creatures, I tried to be consistent. I had a pretty good idea about how the biology of Eden worked and how it evolved, and I also applied what I know about evolution on Earth. For instance, animals are always variations on certain basic underlying body plans – so all vertebrates on Earth have four limbs, two eyes, and no more than five digits- and I tried to apply this to the animals of Eden. Slinkers belong to a multi-limbed class, but all the other land animals have six limbs, two hearts, and large flat eyes. I think this has made my creatures more believable. I hope so anyway.

MB – Is this definitely the end for Eden and if so, what are you working on next?

CB – I’m currently working on a book set in America which creates all kinds of new challenges for me, and makes writing about Eden seem very easy! My next published book, out this year, will be a collection of (non-SF) short stories. I don’t think I will be writing on any more Eden novels, but I quite like the idea of writing an Eden-based story collection at some point, with stories from across the whole history of Eden.

MB – Thanks for your time Chris.

You can follow Chris Beckett on Twitter at @chriszbeckett. Chris’ website can be found at www.chris-beckett.com. All of my reviews of the Eden Trilogy can be found Here. You can purchase all of Chris’ works on Amazon and from all good, and not so good, bookshops.

A meta-finale.

Leave a Reply