John Le Carre is one of those authors whose work has an incredible reach. While the early novels live in “the secret world”, they transcended it by exploring the people that populated them even more than the tradecraft that serviced the plot. And there is the first thing, a spy’s “Tradecraft” is a term Le Carre came up with himself. Going through the DNA of his novels with Alec Lemas, Magnus Pim, Jonathan Pine and, of course, George Smiley, feels like you are entering the world of Thames House (MI:5) and Vauxhall Cross (MI:6) and you are learning things that you shouldn’t. According to Le Carre, you really are not. He made it all up to service his tales and his own service with the Secret and Secret Intelligence Services both brief and, to his own admission, ineffectual. Yet his creations have leap from the pages with such force, the terms he created are now part of the secret world’s lexicon. The man himself, David Cornwell, is as confusing as some of stories are at first glance. Following on from Adam Sisman’s stunning and detailed biography of Le Carre (reviewed here), Le Carre decided to put out his own take on his life. The result is The Pigeon Tunnel, a book considerably shorter than that of his biographer’s.

The title itself relates to a tunnel in Monte Carlo where pigeons were released so that they could be shot for sport by the hotel and casino’s guests. This image haunted the boy who would become Le Carre and was the working title of almost all of his novels, but never used until now. The novels have lives of their own and that is due to the passion that goes into them. It is the early formative years that you see this passion’s seed planted. From the departure of his mother in the middle of the night, to Ronnie, his wide-boy father, to his arrival in Bonn to watch ex-Nazi’s carve up West Germany to suit themselves and cover their past sins. These experiences inform the man, who then bleed these elements into his characters. Early in the book, Le Carre explains that he didn’t keep diaries or notes as such. His notes where in the experience of characters he was creating, trying to see the world through their eyes.

data-animation-override>

“The other scribbles that survive from my travels were made for the most part not by me personally, but by the fictional characters I took along with me for protection when I ventured out into the field. It was from their eye-line, not mine, and in their own words, that the notes were written.”

Taking this pinch of salt early, and with the explanation he is not knowingly getting anything wrong, he launches into his tale. And it is quite a story. Having devoured Sisman’s biography, much was familiar but the style in which it is told is pure Le Carre. The Pigeon Tunnel reads very much as an interconnected series of vignettes that feel like being entertained over dinner by a wonderful host. A host that may be one glass of sherry to the good and monopolising the conversation, but wonderfully entertaining nonetheless. Given that the subtitle of the book is Stories from My Life, this shouldn’t really have been much of a surprises. Within the tales, you see the anger that bubbles within Le Carre and informs the novels he writes. People he meets on his journeys become characters 20 years later. Incidents become plot and spinets of overheard conversation dialog. It is interesting reading Le Carre telling Cornwell’s life, so that you feel that you are learning very little of the man behind the name. While the adventures and travels are brilliantly told, getting under the skin of the man is not what the book is about. For while we get to see where the novels gestated from, Le Carre and Cornwell keep a distance from each other. Again, early in the book, we are told how comforting having a different name to the novelist is and, reading between the lines, we can see that protection extends to this work. We are told that he came to love late and this caused much problem to those around him. Yet he doesn’t explain any further the failure of his first marriage, the affair with Susan Kennaway or the beginning of the life he now has with Jane. But, this, of course, is his prerogative and while he refrains from telling us much of the professional life he lead and those who still may be alive, he very much extends this to his family.

The Le Carre/Harkaway Shelf

While Le Carre is very warm to his friends, the final chapters of the book, relegated there because he didn’t want him muscling in on the story, are about his father, Ronnie Cornwell. Ronnie was a con-man in a Saville Row suit. A charmer who would wine and dine the great and good and leave them to pick up the tab. The tale of growing up with the man is heartbreaking. As is the violence, both physical and phycological, that led to his mother packing one bag and leaving without a word in the middle of the night. Reading the conflict in his relating of this even and to the feelings about his father is truly heartbreaking. When finally meeting up with his mother again, he know how to hug her, her angles seemed wrong. Yet, it made him the perfect recruit into the world he then recreated in his mind’s eye.

The Pigeon Tunnel is a fabulously entertaining journey through John Le Carre’s reminisces. When I finished the book, I found myself with the same feeling as when I finished The Honourable Schoolboy, that it had been a great journey, but that I’d bought the wrong postcards. While I think that a private man is entitled to keep his secrets, perhaps when tackling an autobiography, you can also try to explain your less savoury actions. Still, The Honourable Schoolboy is still my favourite of Le Carre’s work. Possibly because it seems, like Jerry Westerby, to be lost in something wider. I think the expectation of what readers think John Le Carre is and who David Cornwell actually are is what we see in this book. The two very different sides to the coin which, as fans often do, flip to suit our own expectations.

The Pigeon Tunnel by John Le Carre is published by Viking and is out now. Amazon.

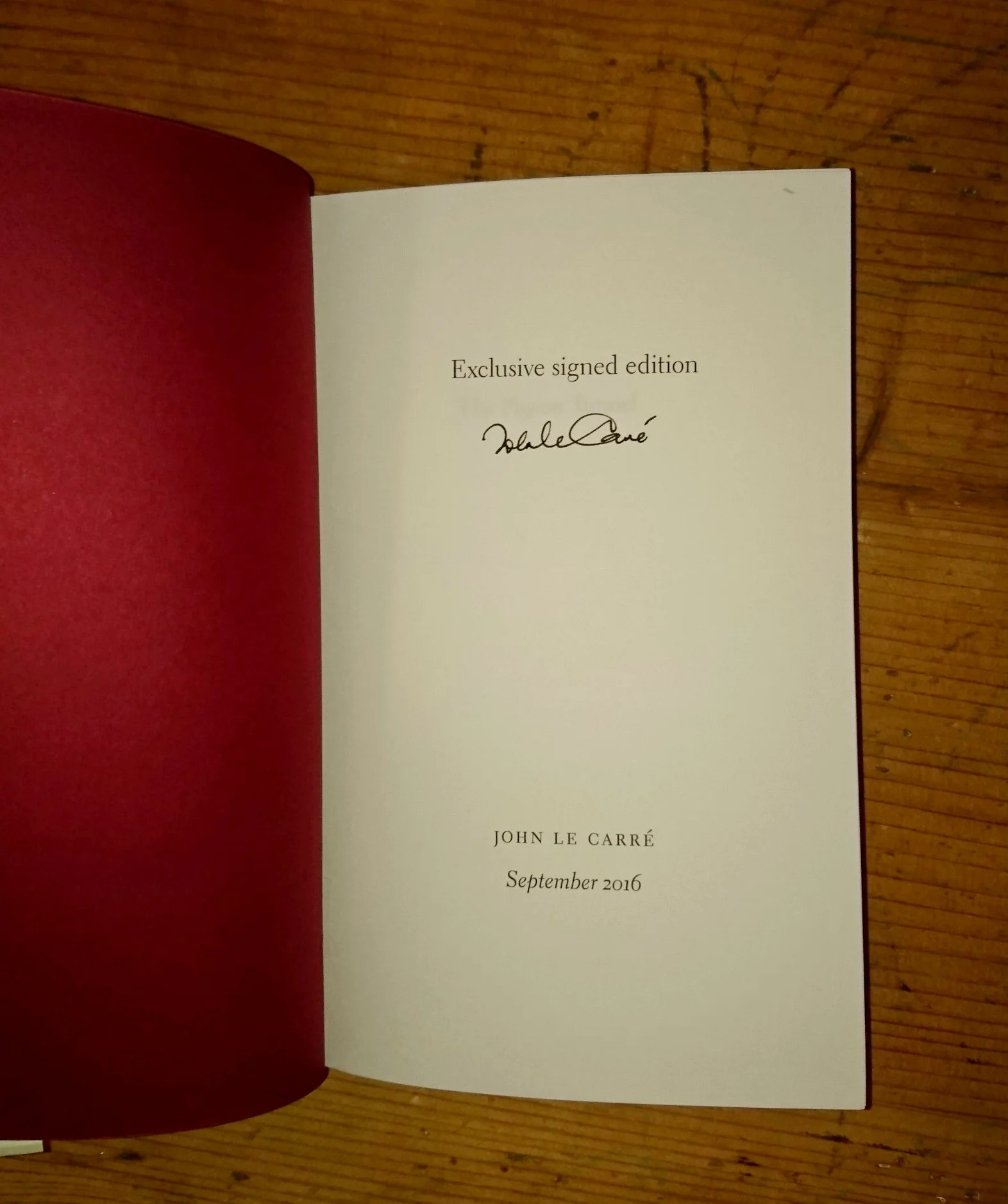

My signed copy.

Leave a Reply