data-animation-override>

“It is up to you to save the world again.”

Two hundred years ago, the single most decisive battle of an age of war was fought. Three armies fought three battles over fours days that would shape Europe, and the world, for the next 100 years. The next time British and Prussian troops would meet in Belgium, they would not be saving Europe, but tearing it apart. The Battle of Waterloo is possibly the most famous battle in history. It has occupied a place in British popular culture, popular history and the British psyche that is rather odd, the British named train stations after it. It’s odd to think that a train station is named after a few square miles of farmland, near a hamlet in the rolling Belgian countryside where 200,000 men crammed onto a tiny battlefield and slaughtered each other.

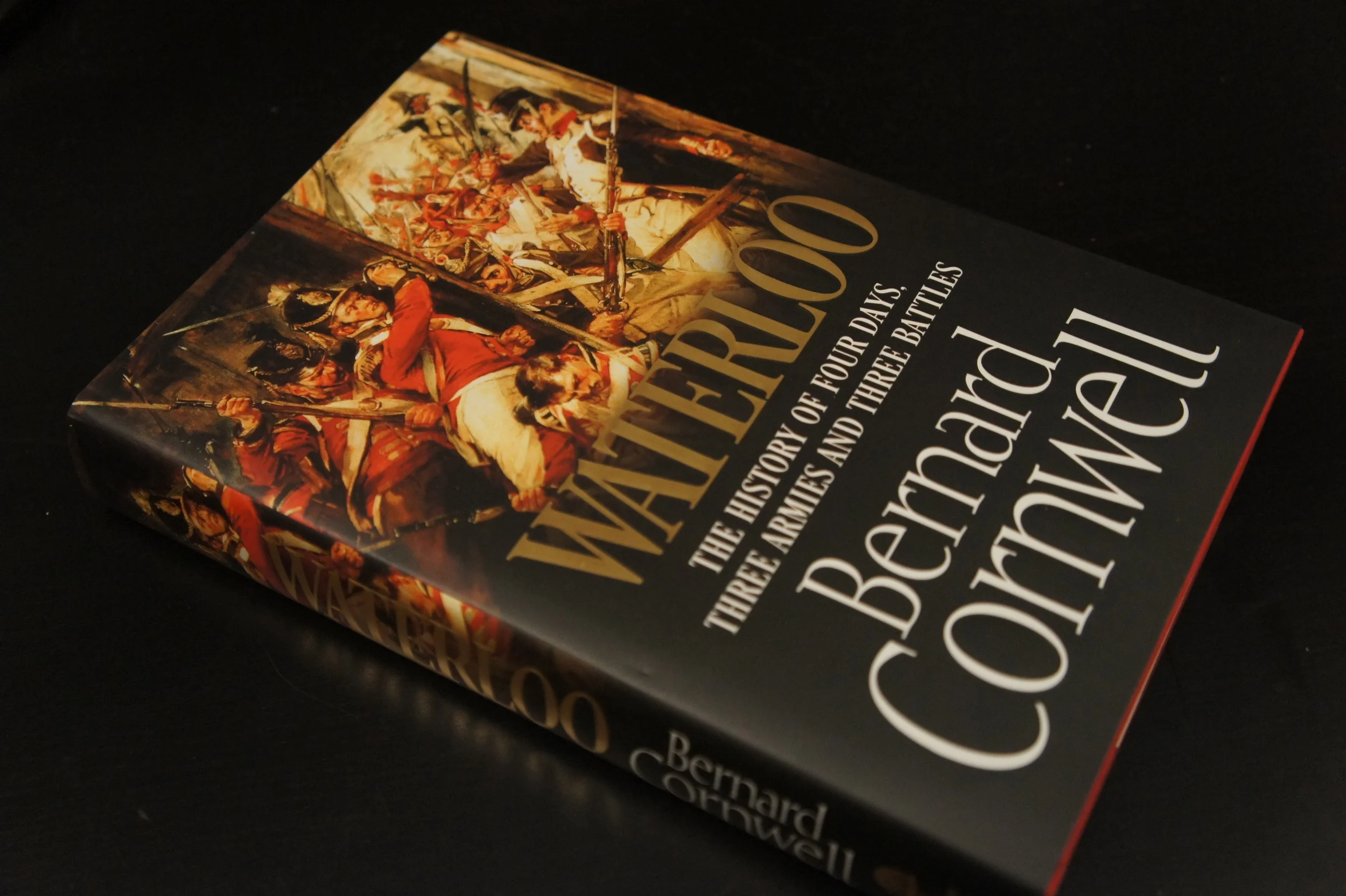

Much has been written about the battle. Victor Hugo wrote the myths about the battle that the French believe to this day in Les Misérables. Peter Hofschroer has written volumes on what he terms The German Victory and when it comes to Britain, well forests have been felled for an almost unending appetite for histories and novels about those four days in June 1815. With the bi-centenary next year, more trees are sacrificed on the altar of Waterloo. Into the fray enters an unlikely author. Having never tackled non-fiction before, Sharpe creator Bernard Cornwell rides in to rescue the reputation of his hero, the Duke of Wellington, in Waterloo: The History of Four Days, Three Armies and Three Battles. The Iron Duke has taken a bit of a battering in recent years, with popular opinion, as we tend to do in Britain far too regularly, turning against the remarkable achievement of Wellington to fight and hold the French off over two bloody days.

My well thumbed copy of Sharpe’s Waterloo

Cornwell is unashamed in support for his hero, but also spreads the credit, and the blame, across the actors, great and small, that make the story so incredible. The thing that everyone agrees on is that it was very close run thing. I’ve read a lot about the battle and there are points in the story, Ney’s cavalry attack, the assault on La Haie Sainte, the advance of the Imperial Guard where, even when you know outcome, history provides the most thrilling story lines, the outcome always feels in the balance. Cornwell has written about the battle before in the penultimate Sharpe novel, Sharpe’s Waterloo. Returning to the subject 24 years later, Cornwell brings his narrative flair for fiction to the tale of Napoleon rolling the dice and attempting to win back Europe one more time. He defines a group of characters on all three sides, who’s letters form the basis of his soldier’s eye narrative. The story of the battles of Ligny, Quatre-Bras and Waterloo are handled with Cornwell’s usual flare and again draws you into the smoke, fire and death of those battles. Throughout, he explains who was there at various points of the battles, the controversies, the mistakes and the dumb luck that took place to shape the history we know. One constant is his villain, William of Orange. He still gets the same treatment as he did in Sharpe’s Waterloo, the joy he had in Sharpe shooting him is replicated on the unknown French skirmisher who actually pulled the trigger and removed the man responsible for the murder of at least two battalions of Anglo-Dutch troops. One of the noticeable things while reading the book, despite the verve with which Cornwell handles the action, is that he repeats himself over numerous occasions. Certain phrases, such as “the rock, paper, scissors of Napoleonic warfare”, and certain anecdotes from the letters of those that were there, reappear in close succession. The repetition jars and eventually become amusing as they pop us less frequently but you have the feeling in they are coming. It is a small criticism of a book that my father and I both devoured, but both noticed the niggle of repetition that points to an author writing a non-fiction work for the first time and/or a slip by his editor.

Overall, it is a superb work of popular fiction. If you are interested in learning about the Waterloo campaign, this is a brilliant place to start. The majority of current works on the battle are rather scholarly, but this is a fantastic ride. Bernard Cornwell does what he does best, he takes the reader and drops them in the mud, looking up at Wellington, astride Copenhagen, calmness personified, orders being given to aides who gallop off up and down the rapidly depleting Red coated line, looking east and praying for battered, bruised 74 year old Prussian nobleman doggedly slogging his way to his friend’s aide. As I finished the book, fittingly on a train bound for London Waterloo, it took me a minute gather myself. Bernard Cornwell has taken me into the breach at Badajoz, into the shield wall with Arthur and Uthred and into the throngs of archers at Crecy and Agincourt, but, while those works of fiction thrill and exhilarate, Waterloo breaks your heart. The image Cornwell constructs of thousands of men, standing, waiting in the mud while tons of metal is flung at them, leaves you feeling exhausted, dirty and saddened. History is written in blood. While reading the numbers of the fallen is one thing, making you feel for them is a special talent, of which Cornwell is a master.

data-animation-override>

“In for a penny, in for a pound.”

Scotland Forever! Lady Elizabeth Butler’s painting of the Charge of the Scots Greys

Leave a Reply